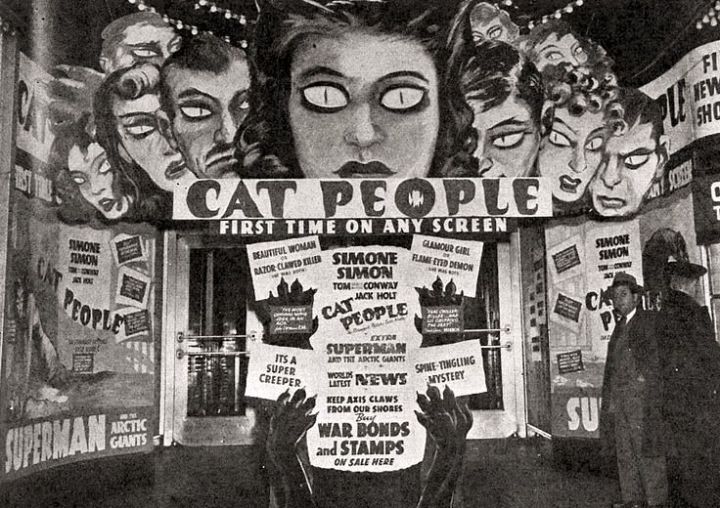

RKO Studios, grumbling over their great misfortune with Orson Welles and Citizen Kane (1941), hired Val Lewton to produce nine low budget horror films. The executives handed Lewton a list of idiotic titles and told him to make some “horror pitchers” that could make money. The RKO execs were looking and hoping for a cheap hack in Lewton. What they got instead was an erudite artist. Numerous directors have imprinted their body of work with their own personality. Few producers have. Val Lewton, did and he began with a film which highlighted two of his own phobias: cats and the fear of being touched.

Cat People (1942) is the first and best of Lewton’s nine RKO films. It was directed by Jacques Tourneur. Tourneur’s entries undeniably stand out among the Lewton series, much like Terence Fisher‘s films did with Hammer Films. For the starring role of Irena, Lewton and Tourneur chose the diminutive beauty and temperamental imported French actress Simone Simon. Simon found Hollywood distasteful, and she remained a perennial outsider.

Simon was the perfect choice for Irena. Much Freudian babble has been written about the film, usually focusing on the fear of sex. Undoubtedly, that is an element in Cat People (one that was vapidly intensified in Paul Schrader‘s 1982 glossy MTV-styled remake). However, Irena’s brooding complexity, amidst a world of two-dimensional bores, is the driving impetus. Predictably, the dullards demonize Irena.

Her husband, Oliver (Kent Smith) is the worst of the lot: banal, hopelessly bourgeois, unimaginative, and attached to hyper-realism: the impotence is on his part, not Irena’s. Oliver can only wither in the company of such fiery intricacy.

Irena’s psychiatrist, Dr. Judd (Tom Conway) tries to convince her that her world is a hopeless fantasy and that she merely needs a real man to show her the light. Irena’s response is to dim her countenance, brandish her claws, and catapult the condescending idiot into oblivion. Good for her.

If only she could have dispatched Oliver in a similar fashion. Marrying the vacuous, phony puritan Oliver is Irena’s downfall. (Off screen, Simone Simon made no such missteps. She never married, and had numerous affairs with artists, including George Gershwin). Almost matching Oliver in monotony is his sort-of girlfriend Alice (Jane Randolph) who feels bad that poor little Oliver has a wife that won’t put out and give him the American dream. Oliver and Alice ban Irena from a stroll through the art museum. Thinking themselves superior in their suburban elitism, Oliver and Alice mantle the attitude that only they are privileged to view the art on display. Perhaps Irena will spend too much time actually looking at the art and disrupt what, to Oliver and Alice, is merely a trendy fashion statement.

Randolph and Smith are perfectly awful in their roles. There is an unintended moment of hilariously wretched acting when Oliver and Alice, pursued by Irena in the form of a panther, hold up a cross and cry: “In the name of God, leave us in peace, Irena!” Disappointingly, we do not witness Irena clawing their suburban dogmas to shreds. Irena, the Eve-like animal and curse upon patriarchal structure, temporarily withdraws.

Cat People is indeed a horror film. Its moments of horror are much celebrated. The above-mentioned pursuit, soaked in expressionist shadows, climaxes in screeching bus; the avatar for Irena’s terror. The swimming pool sequence is an even more discussed classic, deserving of the accolades it has received. Innovative camera angles, lighting, and pacing evoke a blackened, nervous cry. One of the film’s best moments is a more intimate one, with Irena clawing through the cover of a couch.

Lewton’s films serve as a refreshing anti-thesis to the rot that was then being churned out by the Universal factory. RKO executives, initially, did not think so. One such exec walked out of the Cat People screening, convinced of the film’s worthlessness. To his surprise, the film brought in 5 times it’s cost. The unimaginative exec might have been named Oliver.

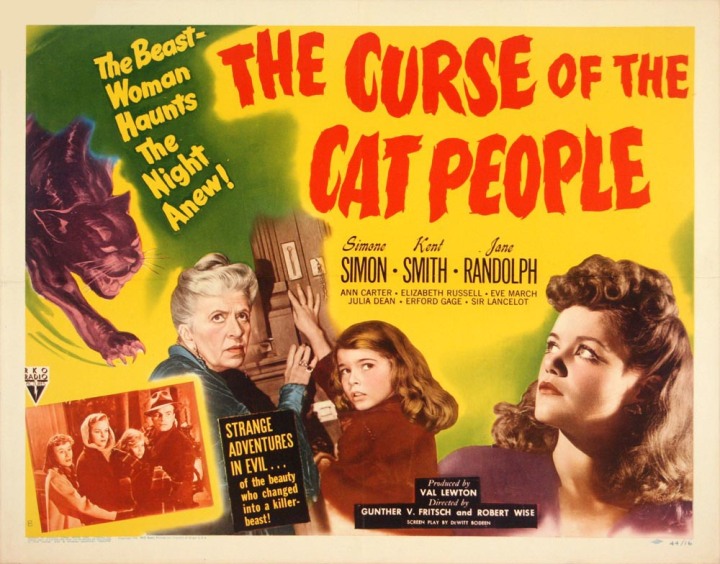

RKO was both surprised and elated over the success of Cat People (1942). Predictably, they ordered a sequel, and handed the title to Lewton: Curse of the Cat People. Lewton, eyes-rolling, took the assignment, but said: “What I’m going to do is make a very delicate story of a child who is on the verge of insanity because she lives in a fantasy world.”

Even today, viewers are split about the sequel. It’s akin to Ridley Scott delivering a prequel to Aliens without a plethora of H.R. Giger monsters. The bourgeoise genre fanboys, wanting only the familiar, will aggressively bellow like the unimaginative and artless Neanderthals they are when confronted with something as fresh as Curse of the Cat People (1944). Although flawed, Curse is a haunting, sublime, cinematic dreamscape.

Irena’s widower from Cat People, Oliver Reed (Kent Smith), is even duller now that he has been married to Alice (Jane Moore) for several years. Upsetting poor Ollie’s Hallmark view of the world is a highly imaginative young daughter, Amy (Ann Carter), who is the occupant of a surreal interior terrain.

Oliver Reed may well serve as a metaphor for a conservative fan base, executive film producers and Promise Keepers. Ollie’s reaction to Amy’s fantasies is archaic hostility. Amy’s preoccupation with the magical constitutes all that is a threat to Ollie. Amy is fully effeminate, artistic, independent, free of the binding status quo.

First, Ollie attempts to mold Amy into a socially acceptable child. Highly introverted, Amy is spurned by the potential friends Ollie tries to force upon her. When chasing after those who reject her, Amy stumbles upon the garden of a faded, elderly actress Mrs. Farren (Julia Dean). Slowly, Amy befriends the lonely woman. Amy reminds Mrs. Farren of a deceased daughter. Mrs. Farren has a grown daughter, Barbara (Elizabeth Russell), but Barbara is consistently rejected by her mother. Mrs. Farren, in a mentally deteriorated state, imagines Barbara to be an impostor and rejects her, withholding maternal love. Barbara, jealous of the attention her mother is showing the stranger Amy, reacts with jealousy.

Amy discovers a photograph of Irena (Simone Simon). Shortly afterwards, a wishing well grants Amy a new friend: Irena. Amy’s garden shimmers with Debussian light when the radiantly passive Irena enters and is welcomed into a picturesque domain.

The edginess of childhood is not glossed over, and a retelling of Irving Washington’s “Legend of Sleepy Hollow” offers a memorable moment of adolescent dread. Amy’s further descent into the magical sends Ollie into a machismo fit. The artistically bankrupt office manager reacts by administering a thrashing. Eventually, Ollie and Barbara accept Amy. Irena has fulfilled her function.

RKO, predictably, reacted to the film with Oliver Reed-inspired hostility and mandated ill-fitting sequences. Gunther von Fritsch, the original director, was replaced by a young Robert Wise, working on his first film. While Curse lacks Jacques Tourneur‘s assured touch, it is, together with The Body Snatcher (1945, also directed by Wise), the best of the non-Tourneur Lewtons.

The great critic James Agee championed Curse of the Cat People. Captivated, Agee wrote that Lewton’s films “are so consistently alive, limber, poetic, humane, so eager toward the possibilities of the screen, and so resolutely against the grain of all we have learned to expect from the big studios.”

Curse of the Cat People was another unexpected critical and box office hit. Yet again, RKO was dumbfounded. Hit or not, they felt betrayed by their producer and Curse, inevitably, served as a prominent nail in Lewton’s RKO coffin.

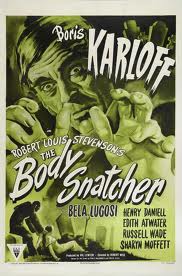

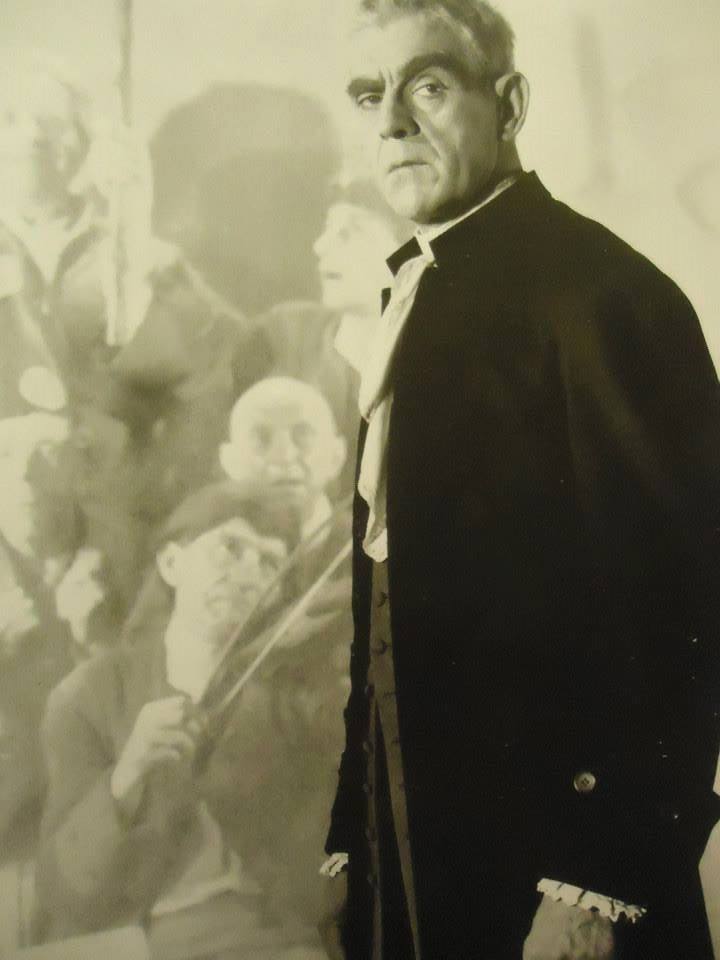

When Val Lewton discovered that RKO was saddling him with star Boris Karloff for a three picture deal, Lewton was not at all happy. The producer had wanted to veer away from the Universal monster-mash factory, which he naturally associated Karloff with. A meeting between Karloff, Lewton, and Robert Wise changed all that. To Lewton’s surprise, Karloff was seeking a change of pace and a return to more literate acting. By the end of that meeting, both Lewton and Wise were charmed by the actor and enthusiastically looking forward to a fulfilling artistic collaboration.

Karloff did three films with Lewton, the other two being Isle of the Dead (1945) and Bedlam (1946) both directed by Mark Robson, a stock RKO director. Lewton should never have hesitated. The Body Snatcher is, easily, the best of the three starring Karloff and the actor almost single-handedly redeems the two Robson films.

Shortly after securing Karloff for The Body Snatcher, RKO signed Bela Lugosi to the film and ordered Lewton to create a role for the former Dracula star. RKO was bound and determined to replicate a Universal horror star extravaganza. Lewton was just as determined to give them something better. Karloff graciously accepted working with his former co-star (this would be their last teaming) and would prove helpful to Lugosi during shooting. While Karloff proved as rewarding an actor as Lewton and Wise hoped he would be, Lugosi’s casting proved problematic. Although Lugosi did turn in one of his few good latter-day performances, the actor’s mental and physical health (a combination of age, drugs, and alcoholism) was a considerable obstacle.

Robert Wise co-directed Curse of the Cat People (1944), but The Body Snatcher was his first solo effort. The film features two superb star performances and several very good character performances, including Lugosi’s. The Body Snatcher, in its pronounced literalness, may lack Lewton favorite Jacques Tourneur‘s poetic aesthetic, but Wise’s fleshier terrain gleans benefits.

Body Snatcher is an adaptation of a Robert Louise Stevenson short story which Val Lewton scripted (under his pseudonym, Carlos Keith) with Philip MacDonald. The film is inspired by and loosely based on the infamous Burke and Hare murders.

Karloff’s performance here is, rightly, one of his most critically acclaimed. Henry Daniel, one of the great character actors, is precision par excellence. The Body Snatcher is an actors’ film, and the two character stars deliver.

Cabman John Gray (Karloff) and Dr. Toddy McFarland (Daniel) are the ambiguous antagonist and protagonist. McFarland is essentially moral, socially accepted, but chillingly cold and obsessively driven to criminal activities. Gray is a social outcast. He is malevolent, manipulative, capable of brutality, blackmail, and murder. Yet, he has a fire in his heart that McFarland lacks.

It’s not even quite that cut and dry. This is Edinburgh in the Victorian era, when celibacy was proof of vocational dedication. McFarland’s celibacy is a facade. He has a secret wife, Meg (Edith Atwater), who poses as his maid. Meg is a seer, with the gift of vision and fire in her bosom. This relationship, so subtly presented, is the heart of McFarland’s hypocrisy and tragedy.

It’s not even quite that cut and dry. This is Edinburgh in the Victorian era, when celibacy was proof of vocational dedication. McFarland’s celibacy is a facade. He has a secret wife, Meg (Edith Atwater), who poses as his maid. Meg is a seer, with the gift of vision and fire in her bosom. This relationship, so subtly presented, is the heart of McFarland’s hypocrisy and tragedy.

Gray is equally complex. He savagely brings a shovel down on the skull of an interruptive dog, yet is capable of tenderness when caressing the cheek of his horse, or petting his cat (after committing murder). Gray has affection for a crippled girl but, without an iota of remorse, murders a blind balladeer (an effective scene, shot in Lewtonesque shadows) to supply the cadaver for the girl’s much-needed surgery.

Lewton and Wise astutely play to Lugosi’s limitations, taking advantage of his language difficulty. Lugosi, as the blackmailing servant Joseph, is slow-witted, slow of speech and slow to grasp what’s happening. Lugosi’s best directors played to his awkward delivery. Some have criticized the brevity of Lugosi’s role here (including Lugosi himself). But it is that brevity which gives power to Lugosi’s role.The role Joseph stands alongside the actor’s best character work. Lugosi’s death scene with Karloff is expertly directed and acted.

Atwater projects strongly in her role. Hers are the needs of a fully rounded woman, her passions and visions aflame underneath the icy exterior McFarland demands of her. She fulfills that role without complaint, self-pity, or self-deceit.

However, the film falters considerably in the roles of McFarland’s assistant Fettes (Russell Wade), the crippled girl Georgina (Sharyn Moffett) and her mother (Rita Corday). These are contrived, saccharine characters.

The finale, straight out of the Stevenson story, is harrowing and sears the conscience.

Jacques Tourneur considered I Walked With A Zombie (1943) his best work. It is an assessment many critics agree with. It is, perhaps, the most apt of Halloween entries. Horror is not at its ripest in 7 foot tall hatchet-welding slashers, brain-eating zombies, or slickly produced libidinous teen-age vampires. Rather, it flourishes in the everyday. Horror is in the droves of people flocking to Wal-Mart to purchase torture porn dressed up as religious dogma, or in the self-made blinders we wear. Producer Val Lewton and director Jacques Tourneur knew this, and delivered a fascinating horror despite being handed one of the most idiotic film titles in cinema history (clearly taken from a pulp source).

Betsy (Frances Dee), a Canadian nurse, has taken a position on the island of St. Sebastian. Betsy’s blinders prevent her from hearing. When a black driver transports her to the Holland plantation, he tells her how slaves were acquired and brought here: “Well, they certainly brought you to a pretty island,” is all she can muster. When she meets her employer, Paul Holland (Tom Conway), he pierces her illusions: “There is no beauty here, the water’s illumination comes from death.” Conway, with his sensual, rich voice, narrates in such a way that Betsy’s love for this tragic figure seems reasonable.

Betsy (Frances Dee), a Canadian nurse, has taken a position on the island of St. Sebastian. Betsy’s blinders prevent her from hearing. When a black driver transports her to the Holland plantation, he tells her how slaves were acquired and brought here: “Well, they certainly brought you to a pretty island,” is all she can muster. When she meets her employer, Paul Holland (Tom Conway), he pierces her illusions: “There is no beauty here, the water’s illumination comes from death.” Conway, with his sensual, rich voice, narrates in such a way that Betsy’s love for this tragic figure seems reasonable.

Betsy is to care for Holland’s wife, Jessica (Christine Gordon), who is the title’s alleged zombie (the opening voice over plays humorously with the title the studio saddled the producers with). Paul’s alcoholic brother Wesley (James Ellison) evades his own guilt and harbors a grudge for imagined ills. The plot is loosely based off a literary source: “Jane Eyre,” with Paul Holland substituting for Rochester. Surprisingly, Hollywood hack Curt Siodmak assisted Ardel Wray in writing the screenplay. The film feels more in line with Wray’s other credits (which include Lewton’s 1943 Leopard Man and 1945 Isle of the Dead).

Even the film’s phantasmagoric qualities are filtered through the poetry of concrete reality. The symbology of the sacrificial St. Sebastian manifests in Betsy. Betsy falls hook line and sinker to the local voodoo lore, fed to her by Jessica’s maid, Alma (Teresa Harris). Although Betsy loves Paul, she is willing to sacrifice her love when she takes his wife Jessica to a voodoo priest for a cure. The ceremony itself is filmed kinetically. The natives are as naïve as Betsy and Wesley, having inherited the misogynistic framework of colonial society and transposed it onto the perennial Eve, Jessica. A frequent theme with Lewton is his refusal to see death solely as a negative. The ambiguous watery catacomb is more gifted relief as opposed to undesired finale.

Tourneur and Lewton’s I Walked With A Zombie is a poetic philter, far removed from Romero’s fantasy apocalypses. And that makes for a refreshing All Hallow’s Eve.

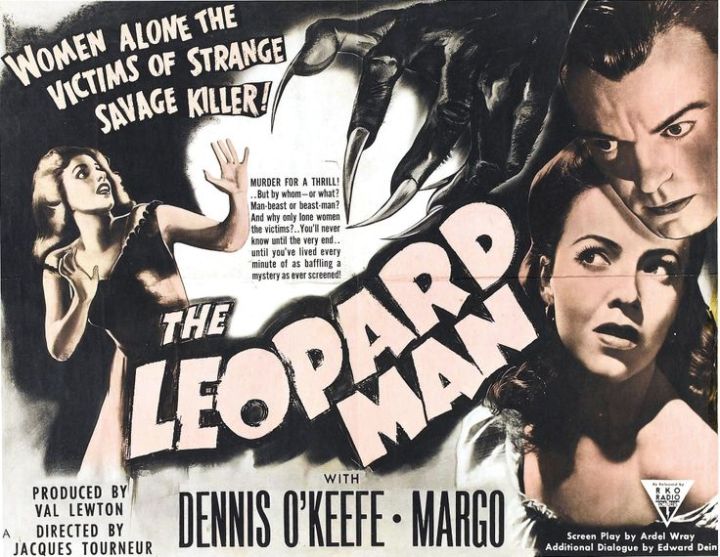

The Leopard Man (1943) is the third and final collaboration between producer Val Lewton and his best director, Jacques Tourneur. It is also, erroneously, often considered their least effort. The Leopard Man was clearly RKO’s attempt to cash in on Universal’s The Wolf Man (1941). But, instead of a wolf turning into a man, we’ll have a leopard! Real clever, imaginative types, these 1940s execs were (of course, now that breed has devolved into the independent trailer trash horror film scene).

Based on a book by Cornell Woolrich (who also wrote the story that inspired Hitchcock’s Rear Window), The Leopard Man is a lucid example of how to produce something worthwhile, even when saddled with a studio-mandated drek title. Perhaps somebody with guts and resources enough will round up the countless perpetrators of low budget horror porn and force a Val Lewton festival upon them. The Leopard Man would be a good starting point.

Like Cat People (1942), The Leopard Man has elements of noir. Set in a sleepy New Mexico town, it’s a film soaked in shadows. A black leopard from a night club act escapes from its leash and runs loose in the town.

Young Teresa Delgado (Margaret Landry) has heard about the leopard on the loose and is afraid. Her mother (Kate Lawson) needs cornmeal. Despite Teresa’s impassioned pleas and objections, Ma Delgado forces her daughter out into the night and deadlocks the door behind her. Cut off from maternal arms, Teresa, cornmeal in hand, is returning to the desired safety of her home. Tourneuer’s use of shadow and light to convey tension and dread is as expert here as in Cat People. It is an extended scene. The callous treatment of Teresa by her mother sows a blackened nightmare. Teresa’s frantic knock on the door, begging for sanctuary from the leopard’s death claws, falls on deaf ears. Ma Delgado’s only concern is the needed ingredient for her meal. By the time Ma realizes that, indeed, her daughter is in danger, the blood, trickling in from under the door, reveals that misplaced priorities and apathy has reaped a slaughter. Teresa is killed off-screen. Instead, Tourneur’s focus is on the most frightening monster of The Leopard Man: a cold parent.

The murders are the film’s focus, which was daring for its time. In that, The Leopard Man may lack the poetic qualities of Cat People and I Walked With A Zombie (1943), but it evokes a unique quality of terror.

The murders are the film’s focus, which was daring for its time. In that, The Leopard Man may lack the poetic qualities of Cat People and I Walked With A Zombie (1943), but it evokes a unique quality of terror.

The second murder takes place in a cemetery. Consuelo is visiting her father’s grave. She is also planning a clandestine meeting with her boyfriend. She promises the keeper that she will not stay long. In looking for her boyfriend, Consuelo instead finds her end. This suspense is heightened and conveyed through the rising sound of rustling branches.

The third murder involves the dancer Clo Clo (Margo) who was responsible for unleashing the beast. A dropped lipstick case and a half-smoked cigarette reveal that she has paid the price, evoking far more horror than a machete-yielding serial killer.

And, as it turns out, there is indeed a serial killer on the loose. The sleuthing is less interesting, as are the men in the film. In this, there is a consistency in Lewton: the heroes are usually, and considerably, duller than the heroines.

Unfortunately, the collaboration between Lewton and Tourneur ended here. Tourneur went onto direct the superb Out of the Past (1947) and Curse of the Demon (1957). Lewton would continue with good, but lesser, directors.

By general consensus, director Mark Robson’s films for Val Lewton are considered to be the weakest of the famous producer’s RKO Pictures output. However, one of them, The Seventh Victim (1943) has garnered a posthumous critical reputation.

Few would dispute the excellence of the Jacques Tourneur/Val Lewton collaborations for RKO, which stand-apart in aesthetics, comparable to Terence Fisher‘s stand-apart films for Hammer (or James Whale‘s stand-apart films for Universal). Yet, despite the drop off in quality, the Robson entries in the Lewton canon could hardly be compared to the execrable lows that Universal and Hammer achieved through hack directors like Erle C. Kenton (1945′s House of Dracula) or Alan Gibson (Dracula A.D. 1972).

Robson’s post-Lewton films validate the claim that he was little more than an assignment director. The nadir of Robson’s directorial career might have been Earthquake (1974). With one or two possible exceptions, Robson’s post-Lewton work was unremarkable, climaxing with the pedestrian action-oater Avalanche Express (1979). This imminently forgettable swan song is only memorable for being a cursed production, during which both Robson and star Robert Shaw died.

Robson would earn a flippant dismissal in the annals of film history, were it not for his collaborations with Lewton. The higher quality of Robson’s work with Lewton strongly indicates that the producer was collaboratively engaged with his directors. Both Lewton and Robson benefited from that partnership. Unfortunately, after Lewton, Robson would never again be afforded such an opportunity.

The Seventh Victim was the first and best of the Robson/Lewton films. Drenched in a noir sheen, it is also the bleakest movie in Lewton’s RKO cannon.The film has an exceptional cast: Kim Hunter as Mary, Tom Conway as Dr. Judd, and Jean Brooks as Jacqueline. As excellent as Hunter and Conway are here, it is Brooks’ raven-like, hypnotic, fiercely haunting performance, exuding a Montgomery Clift-like fragility, which vividly lingers. RKO had no appreciation for such an individualistic, interiorized actor, and unceremoniously released her. She died of extreme malnutrition and alcoholism at the age of 47.

Mary (Hunter) leaves her boarding school to search for her missing sister Jacqueline (Brooks). Jacqueline’s disappearance is linked to her membership in a Satanic cult and her efforts to flee it. Six previous members of the cult have tried to leave, all meeting violent ends. Jacqueline is their potential seventh victim.

The film is awash in doom-laden relentlessness. Unlike many Lewton films, it’s literary references are minimal, although it begins with a quote from a poem by John Dunne. Satan worship, adultery, hints of incest and lesbianism, and suicide merge in the film’s abundant shadows. It’s a miracle the film made it past the Breen office.

Despite all that, this film, along with Curse of the Cat People (1944) is probably Lewton’s most personal, repression being a consistent Lewton theme. In these two films that theme is most pronounced.

While The Seventh Victim has set-pieces that imitate Cat People (1942), they are extremely well executed and enhance the film’s stylishness. Hugh Beaumont plays Jacqueline’s husband, in love with her wife’s sister, Mary. Beaumont is as condescending as he would be, even more famously, as the head of the Beaver household. Tom Conway, as usual, is quintessentially precise. In every way, he is the smooth equal to his more famous sibling, George Sanders. Kim Hunter makes an impressive debut that was the beginning of a lucrative career.

The Ghost Ship (1943) was the second of the Robson/Lewton collaborations. It was largely unavailable for years (due to a plagiarism lawsuit) and the film has a somewhat exaggerated reputation for obscurity.

The story will indeed seem familiar to anyone who has seen Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) or The Caine Mutiny (1954). However, The Ghost Ship is stamped by Lewton’s trademark psychologically stark and suggestive imagery.

The Ghost Ship begins with a typical Lewtonesque prophetic omen. 3rd officer Tom Merriam (Russell Wade) is about to board the Altair. The uncredited Skelton Kaggs plays a mute character who provides voice-over narration, warning the audience what is to about to unfold.

Captain Stone (Richard Dix) takes Merriam under his wing. Stone is a complex and even sympathetic antagonist. He initially sets himself up as a fatherly figure to Merriam. There are identifying bonds between them: both are orphans, both dedicated to service. Yet, the autocratic Stone believes he reserves the right to decide his crew’s life: either to preserve it, or relinquish it. He spares a moth; but, this is juxtaposed against two harrowing, contrasting vignettes.

Captain Stone (Richard Dix) takes Merriam under his wing. Stone is a complex and even sympathetic antagonist. He initially sets himself up as a fatherly figure to Merriam. There are identifying bonds between them: both are orphans, both dedicated to service. Yet, the autocratic Stone believes he reserves the right to decide his crew’s life: either to preserve it, or relinquish it. He spares a moth; but, this is juxtaposed against two harrowing, contrasting vignettes.

In the first, a newly painted, untethered hoist gives way during the night, swinging like a pendulum. In a frenzy, the crew attempt to secure the hook as Stone voyeuristically observes with sadistic euphoria. This scene is a marvel of accomplished editing.

In the second, Stone orchestrates the death of a crew member who dared to question his Captain. The crewman is buried under a heavy anchor. With a simple locking of the door, Stone seals the man’s fate, allowing him to be crushed as the sailors above, continuing to feed chain into the portal, are oblivious to the mounting tragedy below.

Ghost Ship features two more unbearably tense scenes. The first is a precursor to the inevitable deconstruction of the relationship between Stone and Merriam. An emergency appendectomy operation, an incompetent surgeon/captain, and the point of a knife are tools of Lewton’s suspense trade. The second scene evokes “The Tell Tale Heart” from the potential victim’s POV. Here, it is a broken lock which sounds like a Beethovenian fate knocking at the door.

Dix’s Stone is no cardboard villain. He is a fascist allegory, a picture of banality as evil, with a put-upon fiancee waiting for him at the port.

Isle of the Dead (1945) was the first of two Robson/Lewton films starring Boris Karloff. The film was inspired by the expressive Arnold Bocklin’s painting of the same name. This was the most troubled of Lewton’s RKO productions, and the result is an uneven film. Pre-production was hampered by Lewton’s combative relationship with executive producer Jack Gross, who was demanding more full-throttle horror content. Predictably, Lewton resisted. Production itself was held-up due to the hospitalization of star Karloff, who underwent extensive back surgery.

Karloff gives a fine performance, despite questionable casting as a curly-topped, white-haired, sadistic Greek officer. As with most of Lewton’s films, Isle of the Dead is a awash in literary symbology. However, in lacking Tounerur’s organic, poetic philter, Robson’s handling of the material is pronouncedly drier.

Adding to this flaw is the acting of Karloff’s co-stars. The wooden, romantic mooning of Oliver Albrecht (Jason Robards Sr.) over Thea (Ellen Drew) is awkwardly contrived and rings a false note in both the writing and the acting. So too it is with the doomed plague victim Andrew Robbins (Skelton Knaggs). Alan Napier (better known as the butler, Alfred, from the 1960s “Batman” TV series) also appears as an early victim. Generally speaking, the women fare better than their male co-stars. Kathryn Emry as the tragically ill, Poe-like doomed heroine Mary St. Aubyn, Drew as Thea, and Helen Thimig as the the malevolent Madame Kyra flesh out their roles with emotional resonance.

There are references to Greek mythology and religious superstition, but it is the relationship between General Pherides (Karloff) and Kyra that gives meat to the intense climax. Kyra casts suspicion that Thea is a vampire, draining the life-force from St. Aubyn. At first, Pherides mocks Kyra. But, as the plague claims more victims, Pherides begins to believe. Karloff’s Pherides is, of course, the performance of the film. Our introduction to him is his icily pronounced judgment over a fellow officer and friend.

As Albrecht gets to know Pherides, and we learn of the general’s life, it is difficult to reconcile this side of him with what was previously depicted. That is, until he is threatened with crisis. It is then that we come full circle back to our first meeting with him.

The conclusion is pure “The Premature Burial,” giving Mr. Gross his money’s worth. For all of it’s flaws, The Isle of the Dead emerges as refreshing cinematic art, never stooping to level of genre dreck perpetrated by late Universal and Hammer.

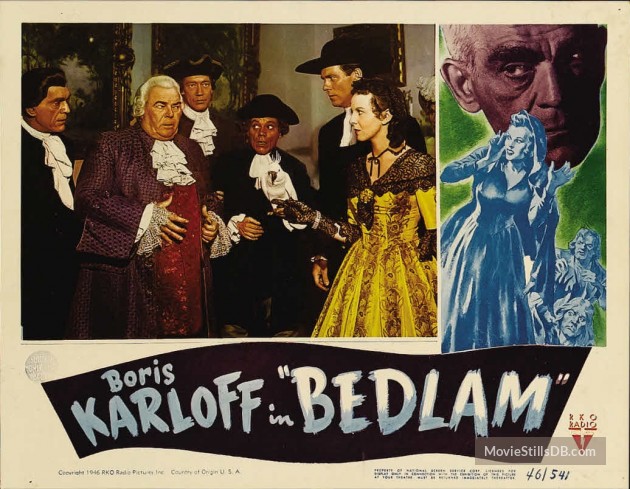

Bedlam (1946) was the last collaboration between this producer and director, and the last Lewton film for RKO. Bedlam was inspired by Plate 8 (“Bedlam”) of William Hogarth’s “The Rake’s Progress” engravings. The picture can partially be seen in the opening credits and is inserted sporadically throughout the film.

Lewton wrote the script under the pen name Carlos Keith. The script and direction share the same weaknesses and strengths as Isle of the Dead. The literariness of the film makes for an arid milieu.

As the sadistic Master Sims, Karloff is atypically void of sympathy. Even when cast as an unquestionable antagonist, Karloff usually managed to infuse some degree of pathos to his villains. Rival genre star Bela Lugosi rarely evoked sympathy and, more often than not, Lugosi’s performances were two-dimensional and cartoonish. To his credit, Karloff never takes his characterization all the way to caricature. Although without identifying empathy, Karloff’s Sims still conveys an emotional arc of substance when he faces his own comeuppance.

Skelton Skaggs and Jason Robards, Sr. again are on hand, albeit briefly (Robards repeats his petrified performance), as is Lewton regular Elizabeth Russell, who delights with a boozy, comic delivery. Karloff and company, however, are upstaged here by the fiery performance of Anna Lee as Nell Bowen.

Nell is the protege of Lord Mortimer (Billy House). Mortimer is the picture of 18th century upper class decadence. Asylum’s Master Sims provides Mortimer with home entertainment via his cast of put-upon “loonies.”

Nell is internally horrified by the treatment of the inmates of St. Mary’s of Bethlehem (known as “Bedlam”), which is noted by the Quaker Hannay (Richard Frasier). In going from spitfire protege, calling out the whited sepulchers, to unjustly committed inmate, Nell, retains her spirited defiance, and it is Hannay who learns a lesson of pragmatic morality over idealized religiosity.

Bedlam, like Isle of the Dead, channels Edgar Allan Poe with Sim’s fate echoing Fortunato’s in “The Cask of Amontillado.” RKO marketed Bedlam as a horror, despite vehement objections from Lewton and Karloff. Predictably, the film failed at the box office. Lewton was blamed and dismissed, Karloff departed, and RKO lost one of its most bankable producer/star teams. Thus, a high mark in cinema was brought to an ignoble end.

Marvellous! I really enjoyed reading this post. I have seen most of these haunting films and am pleased to see them paid proper tribute. Regards Thom