Mahler (1974) is probably Ken Russell`s most personal film. As expected this filmmaker admirably refuses to treat his subject with phony reverence. Rather than a plaster saint here, Mahler is a neurotic, obsessive Jewish composer, hen-pecked husband and an artist whose drive stems from flesh.

Unknown to him at the time, actor Robert Powell’s role as the composer was his audition to play one Jesus of Nazareth for Franco Zeffirelli three years later. Powell’s Mahler is not the Mahler of a Mahler cult. Mahler’s writing is clearly an immense struggle, as is his relationship with his wife, family, colleagues and admirers.

Russell pays Mahler authentic homage in not succumbing to the type of pedestrian biopic cultists tend to favor. That type of bio treatment can be seen in Richard Attenborough’s Chaplin (1992), the kind of well-intentioned but hopelessly unimaginative film one expects from a fan. Julie Taymor`s Across the Universe (2007) takes the opposite approach in her stubborn insistence that the Beatles are not sacred and, thus, aptly produced a film as experimental as were the Beatles themselves (she did Stravinsky and Shakespeare the same honors with Oedipus Rex in 1993 and Titus in 1999).

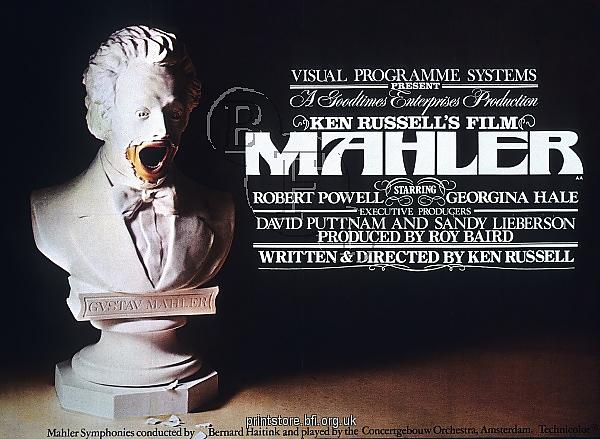

Ever the renegade spirit, Russell, like Taymor, digs into an idiosyncratic interpretation of the artist’s core. Mahler (1974) opens to the first movement of the existential Third Symphony (conducted by Bernard Haitink) juxtaposed against the composer’s hut on a lake, bursting into Promethean flames. Mahler’s mummified wife, Alma (the resplendent Georgina Hale) emerges from a cocoon on the beach and crawls on jagged rocks, struggling to free herself of her bindings. Atop a rock is a bust of her husband, which she embraces and kisses. This dream imagery is explained by a terminally ill Mahler to Alma, who is not amused and misinterprets the dream as a symbolic marital power struggle. Mahler himself fatalistically interprets the dream as one signifying her birth, made possible by his inevitable, impending death. The entire film takes place on Mahler’s final train ride and is interwoven with dreams and flashbacks, piling one existential layer upon another.

Mahler is returning home to Vienna after a disastrous season in at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Mahler was ousted for his unorthodox ways by a Big Apple accustomed to the literalism of a conductor like Toscanini. Mahler, however,is not about to publicly go into the reasons for his return home, especially with a meddlesome reporter who takes the composer’s answers strictly at face value. “Why is everyone so literal these days?” Mahler retorts, dismissing the hack interviewer.

Instead of focusing on documentary points, Russell probes the visions and a past filtered through Mahlerian hues which are, in turn, filtered through Russell’s equally eccentric interpretations.

Mahler espoused big ideas and when asked his religion, he answers defiantly, “Composer.” Indeed, Russell (himself a convert) probes Mahler’s sell-out conversion to Catholicism; clearly, this was strictly a career move on the composer’s part in a blatantly anti-Semitic society. Russell does not shy away from criticism in this sequence (filmed with silent film aesthetics). The cross of Christ and the star of David are placed with the Nazi swastika in an enshrined cave. Mahler bows before money, and Cosima Wagner (Antonia Ellis dressed as an S & M Nazi she-devil) rewards his rejection of Judaism with a roasted (non-kosher) pig, which Mahler bites into with wild abandon. Predictably, Mahler proves to be as agitated a Christian as he was an agitated Jew.

No suffragist, Mahler has been as demanding on his wife as he is on orchestra, insisting that she forgo her own aspirations as a composer and slave in silent servitude to his art, himself, and their children (in that order). This is a hard thing for Alma to forgive; but she also feels her husband’s composition of “Kindertotenlieder” (Songs on the Death of Children) is a case of unforgivably tempting fate that leads to the death of their beloved daughter. Alma is consistently tormented by the image of herself as pedestrian shadow of the genius Gustav. She is left at the bottom of the stairwell as fans adore her returning husband, emphasized by a funeral march movement straight out of Poe. Alma rewards Gustav for all this with an impassioned affair (one of many) and it is a feverishly ill, insecure, humiliated and desperate Mahler who is trying to win back his wife. Powell and Hale are superb in their roles. Hale is delightfully fickle, icy, frustrated, wayward, and conveys every fiber of a woman loved by the artisans. Powell looks the very image of terminal sickness, especially in a symbolic vignette with the reaper facing him in the form of a female African passenger (in voodoo dress) who likens his music to a dance with death. In one sequence Mahler is depicted as a (Stan Laurel-like) clown, with Russell sparing no one in the funeral nightmare, fittingly choreographed to what many consider Mahler’s most surreal work: the Seventh Symphony.

Russell’s film mirrors much in the Seventh. It is a five movement work which begins with an allegro that is part kitsch Viennese waltz, part grotesque military march, energetic and, finally, bittersweet. This opening is followed by the first night music: a child-like walk through the night, replete with cowbells, a giddy dance, and ending with silence. The third movement is the phantasmagoric scherzo; essentially, another night movement that is, by turns, amusing and frightening. A second, amorous night movement follows the scherzo. The Rondo finale is a psychedelic pageant which many critics feel dissipates into complete banality and can be a fitful assertion of life or a dance-til-your-death frenzy.

Naturally, Russell utilizes the scherzo for Mahler’s overheated funeral, brought on by the composer’s heart attack, but the elemental structure of the entire Seventh could be seen as kind of blue print for Russell’s film. Alma mockingly spreads her legs before her dead husband’s coffin and follows that with a nude, coarse grinding strip with Teutonic beefcakes. Her beau, Max (Richard Morant), represents all of her lovers, and he is decked from head to toe as a stormtrooper. Gustav has been buried alive, but this is of no concern to Alma who is lusted after and sensuously pawed over only now, after she has emerged from her husband’s domineering shadow. Mahler is cremated in an oven, but his eyes remain untouched to witness her having the time of her life after his demise, which climaxes with Alma having sex with a gramophone. High art, low camp, sex and death. How better to serve up Gustav Mahler? Mahler’s epic works can be tantalizing, self-absorbed, seemingly disparate mixes of banality and nobility, the profound and the asinine, the intimate and the boisterous, sincere seeking drenched with equally sincere cynicism, and, finally, insatiable curiosity permeated with a whiff of pathos, or, often, deadly bathos.

Composer Arnold Schoenberg hailed the Seventh as the death of romanticism, but he was only half correct. Mahler was still the romantic, and Russell is equally vivid in that depiction as well. Mahler truly loves his wife above all, and he casts a slight smile when he silently looks away from the train (as he often and tellingly does) to observe a couple deep in love at the terminal.

Despite our knowledge of Mahler’s imminent fate; his tumultuous relationship with his wife and his obsession with her many infidelities; his fear of his own mortality; his hallucinatory, self-indulgent expressions; his pathos-laden memories of the past; his insincere conversion; his child-like questioning of existential themes; and his fevered, zealous drive, it is the composer’s buoyant embrace of life that encapsulates Russell’s wonderfully symbolic, baroque vision of an undeniably great and influential artist.