Harry Langdon (June 15, 1884 – December 22, 1944)

Charlie Chaplin said he “only felt threatened by Harry Langdon.” Samuel Becket wanted Langdon to act in his experimental film, but had to use Buster Keaton after Langdon’s early death. James Agee, Kevin Brownlow, Walter Kerr, Robert Youngson, Harold Lloyd and Mack Sennett were among those who sang high praises for Langdon’s art.

Langdon’s characterization expressed the most pronounced silence of the era’s clowns. This is why, despite his fans’ claims (seen on the documentary included on “Lost and Found: The Harry Langdon Collection”), sound proved completely disastrous for him. Langdon’s persona was only suited to the abstract plane that silent cinema offered.

It is easy to see why he appealed so readily to the Surrealists. His persona is dreamlike, subconscious, otherworldly. Langdon’s man-child seems an elfin id. Silence and make-up were existential turpentine for Langdon, removing him, layer-by-layer, from the world as we know it.

Of course, for many, turpentine is unbearable, and Langdon haters will pull out their hair, waiting for him to do something. Even his blink was lethargic. Frank Capra, Langdon’s one-time director and permanent detractor once bitched, “It takes him an hour to get started.” Langdon was the master of anti-reaction and he did more with less than anyone, Keaton included. That’s the magic of the Langdon persona. With the barest minimum, he was able to etch a characterization so vivid, it is second only to Chaplin in identifiability. Langdon’s unique personality accelerated his stardom.

The cause of Langdon’s equally quick fall, after a mere three years, is debated. Certainly, that same personality, combined with his admirable risk-taking, ego, and poor business skills, was partially responsible. But, after he left Sennett for the fascistic First National, both studios released a plethora of his films; the result was an onslaught of Langdon product in 1927, and his considerable fan base went into massive overdose.

Steve Martin tried something similar with a brief series of films that pushed his own boundaries. When the payoff proved commercially lackluster, Martin predictably receded back into the safety of the mainstream. Langdon received no chance for reprieve with First National.This stands in direct contrast to Capra’s self-serving claim that he alone fashioned Langdon’s screen persona. Capra further claimed that the actor had no true understanding of his own persona and when Langdon ventured into edgier territory, over Capra’s populist-minded objections, the star simply imploded. With sound inevitably around the corner, combined with Langdon’s advanced age in comparison to younger rivals, his desire for rapid experimentation is understandable. The risks he took produced an artistic triumph, but a commercial disaster.

He alone was blamed for the disappointing box office results of Three’s A Crowd (1927) and The Chaser (1928). His third self-directed feature for the studio, Heart Trouble (1928), was never released and reportedly was destroyed. By most accounts, it would have proven to be his commercial rebound effort. Lamentably, the film seems to be forever lost.

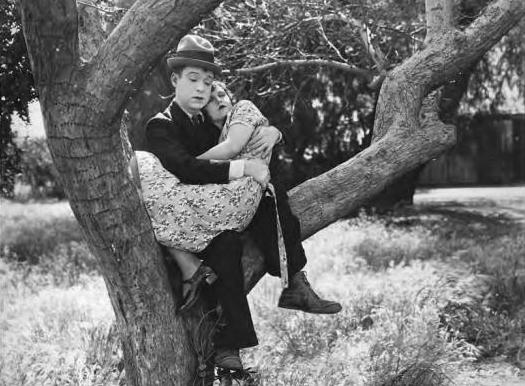

Harry Langdon was and remains an idiosyncratic, enigmatic, minimalist “anti-clown.” For many a novice, he appears a sort of inexplicably surreal forerunner to Stan Laurel’s child-like persona. Yet, unlike Stan, Harry’s character had an amorous nature, which became progressively dark-hued, reaching the breaking point, for early fans at least, when he fantasized about murdering his fiancée in the Capra directed Long Pants (1927), and in his own much maligned, masterpiece of existential pathos, Three’s a Crowd.

When Mack Sennett landed a contract with Langdon in 1924, formulaic slapstick had run its course. Sennett, ever the shrewd businessman, knew he desperately needed a breath of fresh air, and got it in spades with Langdon. Langdon was already forty, considerably older than the energetic, youthful Chaplin, Keaton or Lloyd and already had an impressive critical and popular reputation from his vaudeville act.

Since several studios were vigorously courting Langdon, Sennett was lucky to nab him, and did not intend to waste his investment. This beautifully re-mastered and essential collection from All-Day Entertainment/Facets Video contains the surviving Sennett films, along with a good but repetitive documentary and a few random, painfully wretched, depressing sound shorts on a bonus disc.

The first disc in the “Lost and Found” collection shows Langdon’s persona quickly evolving; that characterization is richly molded within a mere six months. The second and third discs contain the treasure trove. Giving the lie to Capra’s claim that he originated the Langdon character, All Night Long (1924), directed by the underrated Harry Edwards, shows the character already firmly in place and is the first Langdon masterpiece. As one commentator states, these shorts, so detailed in personality and plot, seem very much like feature films. All Night Long pairs Langdon with his two best co-stars; Vernon Dent and Natalie Kingston. These two actors were perfect, complimentary foils for Langdon, and both remain horribly underrated.

Dent might be likened to an Oliver Hardy–type sidekick, except that Dent was a far more versatile actor than Hardy ever was (that is no swipe at Babe). Dent typically played Langdon’s burly Bluto-like bully, but resonated far more depth in his portrayal of Professor McGlumm in His Marriage Wow (1925). Dent’s pessimist professor is downright creepy, matching Langdon’s paused, minimal expressiveness with priceless, under-the-skin glances. Dent’s McGlumm bears an uncanny resemblance to Robert Helpmann’s Child Catcher from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) and, at the end, he reveals himself to be none other than the infamous Barney Google of the 1920’s comic strip.

Kingston is equally priceless: tall, stylishly dark, incredibly sexy, and evoking true, expressionistic danger. She is both Jezebel and Delilah, seducing and attempting to murder Langdon in both Lucky Stars (1925) and Soldier Man (1926). Langdon, Dent and Kingston make for a unique trio in all of their films together. Kingston is Sgt. Dent’s girl in All Night Long, but only until lowly K.P private Langdon unwittingly steals her away.

For his betrayal, Langdon’s private is banished to the war front of the surreal No Man’s Land, only to triumphantly sift through the inexplicable circumstances he finds himself thrown into (he’s akin to Betty Boop’s Minnie The Moocher or Peter Sellers’ Chance the Gardener), and wins Kingston in the process.

Another, uncredited co-star might be the dummy in Feet of Mud (1924), which again co-starred Dent (as Langdon’s football coach) and Kingston (as the rich girlfriend). Through elongated, almost plastic, repetitive reactions ,Langdon interacts with a mannequin, mistaking it for a real person. It is a surreal bit of business Langdon explored time and again.

Along with All Night Long, Lucky Stars and Saturday Afternoon (1926) may be the best of the distinguished lot. In the richly plotted Lucky Stars, Langdon pursues his astrological sign and joins a medicine show. Little doubt, Langdon’s own background colored the tale since heran away from home to join an Indian medicine show at the age of twelve. Dent is marvelous here as Langdon’s seasoned, quack instructor. Dent is equally impressive in Saturday Afternoon (a precursor to many a Laurel and Hardy plot) as Langdon’s good-old-boy date buddy, ambitious to secure an afternoon with a couple of those “tomatoes with the gorgeous lamps.” Langdon’s charming, little boy lost reaction to a kiss shared between Dent and his date is sublime.

In the enormously popular Fiddlesticks (1926) Dent takes on two roles, as Langdon’s fragile fatalism soars the heights that would crystallize in Three’s a Crowd. Langdon propels the viewer deep into the discomfort zone when he dons drag in The Sea Squawk (1925). (Pee Wee Herman masturbating in an adult theater or wearing mirrors on his shoes to look up girls’ dresses has nothing on the disturbing sight of a transvestite Harry!)

The pristine His First Flame (1927) reunites Langdon, Dent and from in Langdon’s first feature, Capra’s The Strong Man (1926). The Strong Man remains Langdon’s most popular film and the one for which he is best remembered.

Langdon took Edwards, Capra, and writer Arthur Ripley to First National with him. The second feature there, Tramp, Tramp, Tramp (1926) went over deadline and over budget for which, unfortunately, Edwards was blamed and fired. All three of these features did well with audiences and critics alike, but it was in the third, Long Pants (1927) that the idyllic working relationship between Capra, Langdon, and Ripley became unraveled.

Capra objected to the film’s darker elements. His conception of the Langdon character was as an innocent child, inexplicably protected by God. But, Langdon, Ripley and Edwards, as seen in the pre-Capra All Night Long, had already developed that character concept. In Long Pants, Ripley and Langdon retained the wonder of Langdon’s man-child, but jettisoned innocence in favor of less sympathetic character flaws. Langdon was selfish, vain, obstinate, stubborn, and even contemplated murder. It was Langdon and Ripley’s two against Capra’s one. The result of the disagreement was Capra’s dismissal, for which the director never forgave the star.

Actually, Capra and Langdon, despite doing good work together, were aesthetically mismatched. Capra always filtered audience taste through his sensibilities, which, of course, helped him become enormously successful. Considering audience taste rarely, if ever, even occurred to Langdon, who simply forged ahead, despite the odds, much like his character.

In Three’s a Crowd, Ripley and Langdon pulled on another rug. Here, Langdon transforms into something resembling Charles Schultz’ perennial loser Charlie Brown and removed any hint of divine intervention. No matter how much we may root for Harry, his character walks away with absolutely nothing. No girl, no future, no promise of Eden. If there is a God, then God mocks Harry. Harry seems to realize this and the film ends with him sending a hurling rock through the storefront window of a local soothsayer, a bit like the unjustly cursed Saul. It was too much for 1927 audiences.

Tramp, Tramp, Tramp (1926), directed by Harry Edwards, was slapstick comedian Harry Langdon‘s first feature for First National. The star was at the height of his meteoric rise and, unknown to him, was a mere year away from his sudden fall. Tramp, Tramp, Tramp is probably the least of Langdon’s silent features, but its merits are considerable.

A dastardly Snidely Whiplash-type landlord has given Harry’s wheelchair bound pappy three months to come up with the rent: ” Son, I hadn’t told you—we don’t own this place—we’ll be put out soon.”

“Does that mean I don’t get my new bicycle?”

Harry can’t keep his mind off Betty, the Burton Shoes billboard girl (Joan Crawford). “Stop dreaming of that girl. The money must be raised in three months—it’s up to you.”

“I’ll get the money in three months if it takes me a year.”

Oh, but wait, which way to go? Primrose Street or the Easiest Way? Which way indeed? Hmmm. Harry ponders, makes a step, steps back, ponders some more. It’s the type of scene that will inspire love of Langdon or pure hate. I opt for the former. As for the Landon haters, unenlightened to the Tao of Langdon—they serve as proof that uninformed opinions simply do not count.

Harry gets and loses a job working for a celebrity cross-country walker. Lo and behold, Burton Shoes is currently sponsoring a cross-country race. If Harry met Betty becomes when Harry met Betty. Hmmm. Billboard girl picture of girl looks like girl on bench. Oh my, let me look see under your hat, Betty. Oh my. Oh my. Same girl. Oh my.

Langdon was, and remains, an acquired taste. The subtextual idea of a Pee Wee Herman/Stan Laurel hybrid lusting after the future Mommie Dearest is the equivalent of nails meet chalkboard for suburbanites, soccer moms, and Curly Howard fans: reason enough for kudos.

Harry enters the race, hoping for the $25,000 grand prize, and putting Ma’s wedding ring on Betty’s finger. His trusty scissors come in handy: Harry’s hotel room is plastered with cutouts of billboard Betty. Harry sleeps with a billboard Betty, much to the chagrin of his competitor, his former boss.

Naturally, there’s trouble along the way, including a few days hard labor for poaching blueberries.

While influences of Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton abound in some of the set-piece vignettes, most importantly Langdon perfects his set-apart persona. Langdon’s wide-eyed innocence, sleepy smile, and surreal pathos probably had a longer lasting latent influence than most of the silent clowns. Stan Laurel, Jacques Tati, Steve Martin, Andy Kaufman, and Paul Ruebens are among those indebted to Langdon’s screen persona.

Long Pants is the film in which that annoying breed known as “slapstick lovers” start their bitching crusade against the “weird” Harry Langdon. Long Pants is also the film that the collaboration between Langdon and Frank Capra came to a crashing halt, due to aesthetic differences which involved the development of Langdon’s character. Langdon and writer Arthur Ripley wanted to take the character into darker territory. Capra vehemently objected and was fired by Langdon, with Langdon anonymously finishing up directorial duties.

Slapstick, as an art form, dates badly and frequently induces more groans than laughs today. Chaplin‘s more ambitious efforts, with (balanced) pathos and dramatic story, telling are of far more interest than his earlier straight-up slapstick efforts for Sennett. Keaton‘s inventiveness and occasional forays into surrealism hold up as his best work and can, up to a point, prove fuel for those arguing for his superiority. Seen today, Langdon was right in his endeavor to make his on-screen characterization darker, more idiosyncratic, more unique, even if naive critics whine that Langdon simply “ceased to be funny” and just “got weird.” It is Langdon’s weirdness that set him apart from the beginning and, while I would probably not, overall, place him in the ranks of a Chaplin or Keaton, I would argue that Langdon etched an influential persona that secures his position as one of the great silent clowns and defies the “forgotten” label often attached to him.

Contemporary audiences, unable to relate to 1927 mores and customs, will certainly find the initial premise of Long Pants unintentionally bizarre in itself. Harry’s father (Alan Roscoe) feels it is time for his boy to grow up and buys him his first pair of long pants, initiating Harry into manhood. Harry’s mother (Gladys Brockwell) is very weepy eyed over the prospect, feeling her little Harry is far too young for long pants and wearing them will only bring trouble. She is correct, as Harry is, psychologically, still a boy. Once Harry loses his short pants (and stockings—an amusingly ‘creepy’ image) and then dons his long pants, he spies a beautiful, exotic woman in a broken down car outside. Mother’s predicted “big trouble” begins its course.

Actually, this is a bad boy habit already formed in Harry, even before his initiation into long pants status, which mama must have sensed. In the opening scene, Harry is lustfully looking at girls from his attic window.

Harry jumps on his bicycle to get a closer look at this woman in the car, who is in fact the wanted criminal Bebe Blair (Alma Bennett). Bebe is temporarily stranded due to a flat tire. Her chauffeur is fixing the problem when Harry arrives. Unknown to Harry, Bebe is smuggling nose powder for her criminal boyfriend. Harry wheels around Bebe’s car, showing off his newly acquired long pants along with his considerable bike riding skills. Bebe is equally annoyed and amused by this man-child stranger. She gives Harry a kiss in an effort to get rid of him, but, of course, Bebe’s wet lips have the opposite effect on poor Harry. Bebe vamps him and he is now convinced that he must marry Bebe.

Harry’s mother and father have different plans. They want Harry to marry Priscilla (Priscilla Bonner, who starred with Langdon in Capra’s popular Strong Man from the previous year). Indeed, Priscilla is the type of gal to bring home to mama; the only problem is, compared to Bebe, Priscilla seems to be a bit dull. Priscilla and Harry’s parents are insistent on the wedding taking place despite Harry’s new-found infatuation for Bebe. When Harry finds out that his “true love” Bebe has been caught and imprisoned, Harry decides the only thing left to do is kill Priscilla. Here, Langdon foreshadows dark hued man-child types such as Steve Martin (when he counted) and Pee Wee Herman (Stan Laurel, often compared to Langdon, was simply a neutered version). Watching little Harry fantasize about murdering his bride in the woods on their wedding day can be as disconcerting as amorous little boy Pee Wee looking up girls’ skirts with a mirror tied to his shoe.

It is the contrasted imagery and characterization that is disturbing and hilarious. Harry’s screen persona went further into the dark side with the 1928 film, The Chaser, directed by Langdon (in that film, Harry’s man-child could be seen attempting suicide in drag).

Of course, nothing turns out as Harry hopes, but all still ends happily ever after for the Boy. Despite the happy conclusion, Long Pants ranks as one of the most authentically strange comedies of early cinema. In less than a year, Langdon would go several steps further, lose the up-beat ending, and propel his character into a total loser, Charlie Brown-type territory. Consequently, he would lose his too-easily shocked audience as well. Langdon was certainly ahead of his time and lost everything in his battle for individuality. However, the passage of time indicates little Harry won his standout war after all. He remains unique.

Approaching Harry Langdon’s Three’s a Crowd is a loaded task. This film, possibly more than other from silent cinema, comes with an almost legendary amount of vehemently negative appendage. One time collaborator Frank Capra played the self-serving spin doctor in film history’s assessment of Langdon and this film. He characterized Langdon’s directorial debut as unchecked egotism run amok, resulting in a career destroying, poorly managed misfire and disaster.

That assessment is a grotesque and clueless mockery of film criticism.

The startlingly inept critical consensus, in it’s failure to recognize this dark horse, existentialist, Tao masterpiece, reveals far more about reviewers than it does this film. The complete failure of that consensus to rise to Langdon’s artistic challenges, to appreciate his risk taking towards a highly individualistic texture of this most compelling purist art of silent cinema, only serves to validate the inherent and prevailing laziness in the art of film criticism.

Capra’s statements are frequently suspect. As superb a craftsman as Frank Capra was, he also made amazingly asinine, disparaging remarks regarding European film’s penchant for treating the medium as an art form as opposed to populist entertainment. So, likewise, Capra’s inability to fully grasp Langdon’s desired aesthetic goals and intentions is both understandable and predictable. Samuel Beckett and James Agee are considerably far more trustworthy and reliable in regards to the artistry of Harry Langdon.

Capra credited himself for developing Langdon’s character through several shorts, along with the features Strongmanand Long Pants. Actually, Langdon had thrived as a vaudeville act for twenty years and had appeared in over a dozen shorts before he and Capra began their brief, ill-fated collaboration.

Aesthetically, Langdon was Capra’s antithesis and the surprise is not that the two artists would have a falling out, or that Langdon’s stardom would be over almost as soon as it began, but that he ever achieved stardom in the first place. Langdon began edging his character into darker territory in the Capra directed Long Pants, and it was this that lead to their inevitable break.

Three’s a Crowd is quintessential Langdon unplugged and it’s existence is almost a miracle.

Cubist, minimalist, enigmatic, avant-garde,personal, painterly,static, dream-like, lethargically paced, performance art: all these terms apply to Three’s a Crowd.

The set pieces immediately convey the film’s genteel, surreal aura. A milkman, making his early delivery at dawn, is the only sign of life in an otherwise empty city street. Inside Harry’s apartment, an alarm clock vibrates. The camera seems eerily frozen on the clock, almost as if a still photograph. Harry sits up in bed, half asleep,a long stillness envelops the scene. The street outside is now bustling with activity. Back inside the apartment, Harry still sits in that state between sleeping and waking. The alarm clock continues to vibrate. This establishes the character as one who is apart from the world around him. His face barely registers at all and only the slightest of gestures even indicates Harry is actually alive. An eyebrow is arched, the corner of his mouth oh so slowly curls upward.

Harry’s boss, Arthur Thalasso, is outside, yelling, trying to wake his tardy employee. Soon, Thalasso’s family is introduced, then poetically contrasted, with Harry’s solitary existence and all consuming loneliness.

Harry discovers a beaten up rag doll; a metaphoric symbol for the sense of family which cruelly evades him.

Capra described the development of the Langdon persona as an innocent,who triumphs because he is protected by God. Langdon takes away the divine safety net and took great risk in re-casting his character as a sort of dark-hued, sexually repressed, perennial loser Charlie Brown, alternately attractive to and rejected by women. Despite doing everything right and having the most noble of intentions, this Voltaire-worthy Harry completely fails, and idea is the Divine has a sadistic last laugh at his pathetic creation’s futile attempts.

In addition to inanimate objects (the rag doll), Langdon uses nature’s animals and references to animals to metaphorically compound the salt rubbed into the wounds of his much put upon character. A pigeon brings an anonymous love letter to Thalasso’s wife. Thalasso is convinced it comes from Langdon and a chase ensues. Later, when Langdon discovers a nearly dead half-frozen girl, who he believes to the woman of his dreams, he deduces she is pregnant and ready to deliver. He looks up at her, lying in the safety of his bed, then at the booties in her blanket, then back up at the woman, then at the booties again. His face is still frozen, much as she was frozen, for what seems like the longest moment, as he is methodically taking it all in. Finally, he registers a slight twitch and drops the spoonful of medicine he is about to give her. He flees his apartment, down the long, warped stairway that is shown repeatedly throughout the film. He opens a window and yells inside, “Help, Storks!” An army of women and doctors swarm his apartment, keeping him outside, standing so alone, unsure what to do next.

He has a toy rifle, a drum set, various toys, all for this miracle gift of a holy child, but stands there for half an eternity in complete confusion and bewilderment.

Like Saul consulting the soothsayer, Harry consults a palm reader, to assure him this is all going to turn out all right, that the woman’s husband will not return to claim the wife and child who are, for the moment, Harry’s dream of a family finally personified.

However, like Saul, Harry is at the mercy of God’s humor and, indeed, the husband does indeed return to claim what is his. A surreal dream, a boxing match between Langdon and the husband refereed by Thalasso is only witnessed by the prized woman and child, encased in an opaque, blackened world. Harry wears an over-sized boxing glove, looks at this dream family with the slightest of smiles, points to his glove, then to the husband, slow blinks as the husband strikes a highly theatrical battle pose and…

…Naturally, Harry loses and his dream family is taken away. When the woman of his dreams embraces her husband, Harry looks ups at them, in complete silence, looks at his palm, reminded of the oh so cruel, oh so wrong prediction, then back at this real family, utterly helpless.

Harry returns to the palm reading shop. He raises the brick in his hand to smash the windows, thinks better of it, raises his hand again, decides not to after all and discards the brick, only to see it fly into a wine barrel, which goes crashing into the shop window. Harry retreats up the long winding stairway to disappear into the safety of his lonely home, his dreams as smashed as that window.

The bleakness of Three’s a Crowd is worthy of Beckett, rivals the best of Chaplin, and stands apart as THE unjustly maligned, hopelessly misunderstood, dark horse masterpiece of silent cinema. Fans of silent comedy have often expressed disappointment in this film, citing that it is simply not funny. Similarly, Tom Hanks fans initially resisted his venturing past the expected comedies. Three’s a Crowd defies genre. It is not a comedy, but the purest expression of Langdon’s standout art,which refuses to be pigeonholed. Langdon got his start in film at a much later age than his contemporaries and he always seemed the antithesis of Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd; so his evolution into something even starker, less definable, was the most predictable outcome of Langdon’s career, and then only in retrospect. It is unfortunate that Langdon was not permitted to develop his art and character, but it’s almost a miracle he was allowed to in the first place and this resulting film is his testament. Many of his earlier films for Mack Sennett, while uniquely different, still seem very much expressions of their time, as do the Capra films, but Three’s a Crowd went further and, consequently, stands out and alone as an original, modernist misfit work. It’s, and Langdon’s, time has come.

The Chaser (1928) was Harry Langdon‘s second directorial feature for First National studios. His third and final feature, Heart Trouble (1928) is considered lost. The few who did see Heart Trouble claimed that it could have restored Langdon to prominence. However, by then First National had written their star off, canceled his contract and punished his risk-taking by yanking Heart Trouble. In most likelihood the studio destroyed all the copies.

In his review of Chuck Harter and Michael Hayde’s book “Little Elf: A Celebration of Harry Langdon,” Leonard Maltin writes: “Harter and Hayde are so pro-Langdon that they feel it necessary to disparage Frank Capra [who directed Langdon’s first film] at every opportunity… the authors take heavy-handed swipes at Capra at every opportunity, ignoring the fact that Langdon’s features did take a nosedive after the collaborators parted company. I remember sitting with an audience stunned into silence as we watched Three’s A Crowd and The Chaser when Raymond Rohauer first presented them theatrically in 1971. They are painfully unfunny. There were other factors that worked against these late-silent features aside from Capra’s departure, but Langdon was not destined to succeed as his own producer, as this book explores in detail.”

Maltin, in his turn, takes the tried and true route of putting Capra on a pedestal, while failing to grasp the nature of Langdon’s art as Langdon envisioned it. Neither of Langdon’s surviving features attempt to be typical period comedies. While Capra’s status as a consummate commercial filmmaker is well deserved, his numerous comments regarding European film, experimentalism, and film as an art form are embarrassingly sophomoric. Capra’s bourgeoisie elitism is so pronounced as to render useless his comments regarding Langdon’s aesthetic choices.

The European avant-garde and the Surrealists predictably had a better grasp on what Langdon was trying to accomplish. A revealing example might be found in Wheeler Dixon’s “The Films of Jean-Luc Godard.” Dixon writes that for the script of his film, Prenom: Carmen (1983) Godard cited Beethoven’s notebooks, Rodin’s sculptures and Harry Langdon as inspirations.

In his New Yorker review of The Chaser, Richard Brody writes: “as a director, Langdon was far more radical and original than Capra ever was, which accounts for the audience’s rejection of his films.Three’s a Crowd, from 1927, is a grimly Sisyphean comedy of a lonely man in quest of a family, and its slapstick brilliance is smeared with a mire of poverty that few dramas could rival. In The Chaser, Langdon’s directorial originality fuses remarkably with his unique performance style: he gives himself long, static, and obsessional closeups of a sort that wouldn’t be seen again until the rise of the overtly modernist cinema of the nineteen-sixties. It’s time to remember Langdon as a director, too.”

As with Three’s a Crowd, Arthur Ripley provided the story for The Chaser. The movie opens with wife (Gladys McConnel) berating Husband (Langdon) on the telephone. Husband claims to be at the lodge, but it is past 8:30! Wife’s Mother (Helen Hayward) joins her daughter in castigating Husband. Langdon’s camera lingers on Wife and Mother’s chastising for such an extended time, that it becomes progressively surreal, like a dissonant string duet. Langdon cuts to Husband, on his end, doing nothing for an elongated span of time. Eventually, Husband lethargically emerges from his lifelessness, but until then, the scene could almost pass for a still photograph. Actually, as we soon learn, Husband is engaging in voyeurism at a hedonistic party. Husband does not join in the activities himself. His lack of reaction on the telephone, coupled with his failure to join the party, strongly suggest an impotent character, an idea which will be reinforced later.

Wife and Mother go to court. Judge (Charles Thurston) denies a divorce and instead sentences Husband to 30 days of gender reassessment. Simply put, Judge forces Husband to be Wife for a month, while Wife gets to be husband. The inserts of newspaper headlines, announcing Judge’s sentence on Husband are intentionally childlike, as if culled from a dream.

From hère, The Chaser becomes postmodern.

Now parading around the house in a skirt, Husband (now Wife) sends Wife (now Husband) off to work.

A bill collector arrives, seeking a year-long overdue payment for a baby carriage. Wife calls Husband to ask. Absolutely not. We will not be needing it. The impotent Langdon is forced to return the familial dream.

After the amorous bill collector is sent a packing, the iceman cometh. After the iceman sneaks a kiss, Langdon decides on suicide. A long extended sequence on various methods of attempted self-destruction follows. When all else fails, go play golf with a buddy from the party.

Shorn of his skirt and adorned in his swashbuckling lodge outfit, Langdon reclaims his manhood with a near lethal kiss planted on a couple of bathing beauties at the golf course. This, of course, sends him back to Wife fully revived.

A sequence involving Husband mistaken for a ghost will later influence Stan Laurel.

A small slice of Langdon’s late 1920 audience had stayed with him. However, the site of the star in drag, mistakenly believing he has laid an egg and attempting suicide, rendered them aghast. The Chaser sent Langdon’s dwindling audience packing.

Posthumously, Langdon had his defenders . The critic James Agee was among them. In his Life magazine essay, Agee wrote: “Langdon had one queerly toned, unique little reed, but out of it he could get incredible melodies. Whatever else the others might be doing, they all used more or less elaborate physical comedy; Langdon showed how little of that one might use and still be a great silent-screen comedian. Twitches of his faces were signals of tiny discomforts too slowly registered by a tinier brain; quick, squirty little smiles showed his almost prehuman pleasures, his incurably premature trustfulness. He was a virtuoso of hesitations and of delicately indecisive motions. He was as remarkable a master as Chaplin of subtle emotional and mental process and operated much more at leisure.”

This is a repost of individual Langdon articles.