As a child of the 60s and 70s, I grew up reading about Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), but having been banned in several countries, it was never shown on television and remained-for me-something akin to a “lost film,” achieving mythical status. Then, in the early 80s, with the advent of VCRS, video stores, and VHS, Freaks suddenly was rediscovered. Costing $100.00, I ordered my copy. It was the full feature movie I purchased (excluding the 8MM Chaplin shorts we used to order from Blackhawk Films). When a work of art achieves legendary status, it can fail to live up to its reputation. The Ghoul (1933) with Boris Karloff and Ernest Thesiger (both from Bride Of Frankenstein, 1935) was such an example when I finally viewed it after having read about it for twenty years. Freaks was different. It retained its power and became an anthem; a source of identification to a young art school student. I had previously read of Browning’s uncomfortability with sound and agreed that it would have been even more shocking as a silent, but the awkward line-reading of non-actor freaks (Harry Earles, etc) rendered it powerfully authentic. From there, I explored the films of Tod Browning, discovering his body of art that lead to Freaks, lifetime obsessions, and one of the most unsetlling actor/director collaborations in the history of cinema.

Although Lon Chaney has two roles in Outside the Law (1920), he is

not the star; rather, the film features early Tod Browning favorite Priscilla

Dean who plays Silky Moll, daughter of mobster Silent Madden (Ralph Lewis). Both are attempting to reform under the guidance of Confucian Master Chang Lo

(E. Alyn Warren). Black Mike Sylva (Chaney) interrupts the reformation by framing Silent Madden for murder. Silky, like Lorraine Lavond in Browning’s later The Devil Doll (1939), now has a wrongly imprisoned father.

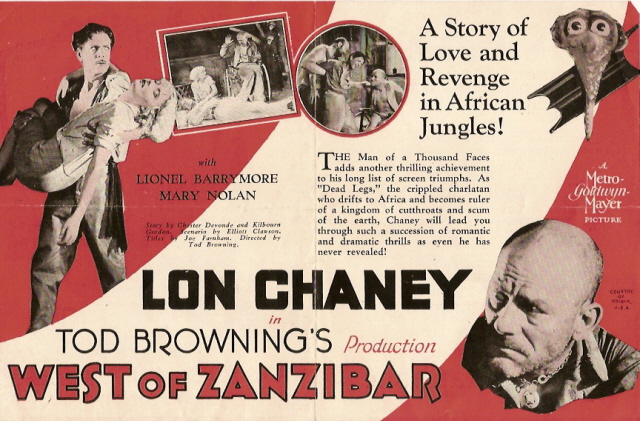

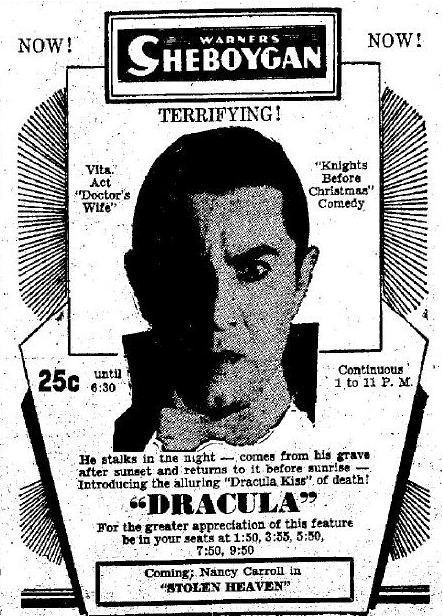

Silky and Dapper Bill Ballard plan a jewel heist with Black Mike. Unknown to Mike, Silky is aware of his betrayal of her father and, with Bill, she double-crosses her father’s Judas. Escaping with the heisted jewels, Silky and Bill hole up in an apartment and the time spent in such a claustrophobic setting is awash with religious symbolism, which points to transformation. Browning, a Mason, repeatedly used religious imagery and themes: In West of Zanzibar (1928) Phroso stands in for the self-martyred Christ and calls upon divine justice under the image of the Virgin. In The Show (1927), the sadomasochistic drama of Salome is reenacted and almost played out in the actors’ lives (Martinu’s

opera ‘The Greek Passion’ would explore that possibility to a more jarring, degree). East is East 1929) utilizes Buddhist and Catholic symbology. Priests and crucifixes play important parts in The Unholy Three (1925), Road to Mandalay (1926), Dracula (1931-

possibly the most religious of the Universal Horror films) and Mark of the

Vampire (1935).

In Outside The Law, Bill tries to convince Silky that they can have a normal life. Puppy

dogs and small boys begin to have effect on Silky, but it is not until she sees

the shadow of the cross in her apartment that her tough facade gives way. Browning

is not one to allow for a genuinely supernatural mode of transformation and

reveals that the cross shadow is merely a broken kite, but its psychological

effect on Silky is manifested in her actions, and her beauty. Bill notices the

origin of the cross shadow and, realizing that Silky’s naive interpretation of

that image has inspired her to renounce her crimes, Bill allows her to continue

in that naivete. He draws the blind so she cannot see the actual source of her inspiration. Justification By Imagination, baby. As Silky begins to drift away from a life of bitterness and crime, towards redemption, she physically grows more beautiful (a transformation achieved through soft lighting and composition). It is not the inspired symbology of the cross alone, but the prophecy of Chang Lo that frames the outcome. Chang Lo has been consistent in his belief that Silky will reform and he strikes a deal with the investigating constable that, should Silky return the jewels, all charges have to be dropped. Here again, Browning’s heart is too much with the criminal to allow for a full-blown punishment, something that later Hays Code Hollywood would demand.

Chaney’s small bit as Ah Wing is so subtle and effective as to almost be unnoticeable. Browning remade Outside the Law in 1930. The remake starred Edward G. Robinson and received comparatively poor reviews. While the remake is not available on DVD, this original is. Kino Video has done a good job in its presentation, but the last quarter of the film is marred by nitrate deterioration, which is not altogether intrusive to viewing.

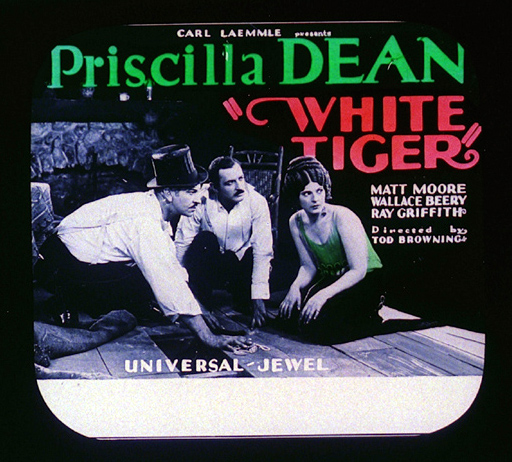

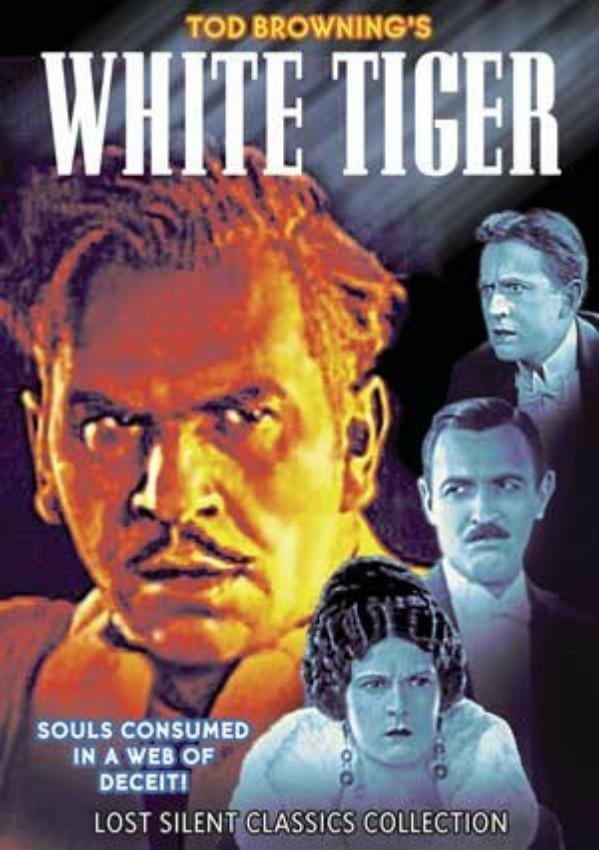

Tod Browning’s White Tiger (1923) finds the director re-visiting intimate motifs and has an unusual connection to Edgar Allan Poe (Browning, who has often been referred to as the Poe of cinema, listed the classic author as his favorite). In 1836, Poe wrote an expose of the touring “Mechanical Chess Player” Automaton. In the expose Poe revealed that inside this mechanical chess player was a concealed, quite human operator. Poe’s article was the seed for Browning’s film, which Browning co-wrote with screenwriter Charles Kenyon.

White Tiger stars Browning Priscilla Dean, Raymond Griffith and Walter Beery. Griffith, who got his start with Mack Sennett, was once considered a rival to both Chaplin and Keaton. However, due to a childhood injury to his vocal cords, Griffith was practically mute, quashing any chance he might have later had for surviving sound film. Most of Griffith’s films are lost, but his most celebrated film, Hands Up (1926), a civil war comedy, survives, and is thought, by some, to be nearly as good as Keaton’s (somewhat overrated) The General from the same year. Although that comparison is highly debatable, Hands Up is a unique film and worth seeing. It is available from Grapevine Video, but otherwise is hard to find.

Griffith’s screen persona was that of a debonair comedian, ala Max Linder, but Browning used him quite differently. Griffith plays Roy Donovan. Sylvia (Dean) is Roy’s sister, but they are separated at childhood when Hawkes (Beery) betrays their father, Mike Donovan (Alfred Allen), which results in Mike’s murder. Hawkes takes Sylvia with him. She believes her brother has also died and is unaware that Hawkes was her father’s Judas.

Years later, Sylvia is a professional pickpocket. She is under the guardianship of Hawkes, who now goes by the new identity of Count Donelli. Sylvia stakes out her victims at the London Wax Museum. There she meets The Kid, who, unknown to her, is her long lost brother, Roy. Roy has his own nefarious gig; the Mechanical Chess Player. When Sylvia introduces the Kid to her “father,” Count Donelli, the three form an unholy alliance, which leads them and the Mechanical Chess Player to a new land of opportunity in America.

Roy develops incestuous feelings for Sylvia (of course, he is still unaware that she is his sibling), which leads to jealousy when Sylvia falls for goody two shoe Dick Longworth (Matt Moore). Tension between the unholy three builds with the arrival of Dick. After a jewelry heist in a mansion, utilizing the Mechanical Chess Player, the trio hole up at a claustrophobic cabin in the mountains. The final quarter of the film casts a Poe-like eye on imagined (and real) enemies. Mistrust between the trio is sowed and much coffee is downed, in an effort to stay awake and keep an eye on each other and the heisted, hidden jewelry.

The truth about Hawk’s betrayal of Sylvia’s real father comes out, as does the revelation that the Kid is none other than her brother. The Oedipal killing of a (surrogate) father, mistrust among a trio of criminals, theft of jewels, false identities, the double cross, staged gimmickry, deception (which the spectator audience is privy to), latent incest, followed by jealousy for a righteous rival, a claustrophobic, getaway retreat, and a finale in which one of the criminals deeds goes unpunished are familial Browning themes. Poe’s deceptive Mechanical Chess Player is a bizarre, added quirk.

According to several Browning biographers, acquaintances of the director and his wife; Alice, would often be forced to lock up the jewelry when the two came to visit because the Brownings had a notorious reputation for swiping any stones they could get their hands on. At least Tod Browning’s empathy for the criminal mindset was an honest one.

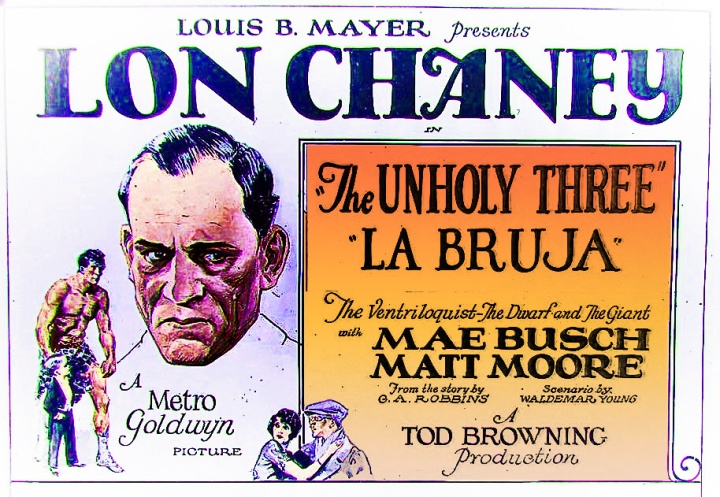

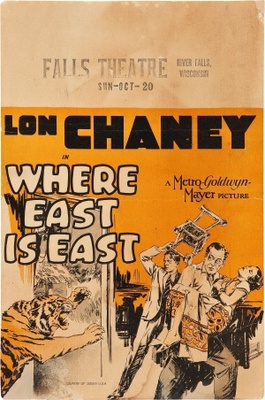

In 2011, Warner Brothers released a series of Lon Chaney films on DVD. Of these, the 1925 Unholy Three, directed by Tod Browning, is of considerable interest. The Tod Browning/Lon Chaney collaborations, The Unknown (1927) and the photo still reconstruction of the legendary, lost London After Midnight (1927) were released a few years ago on a box set highlighting the actor. Before that, Kino previously released the first two films Browning made with Chaney, The Wicked Darling (1919) and Outside the Law (1920). Their The Big City (1928) also seems to be forever lost, which leaves four neglected films; *Where East is East (1929), West of Zanzibar (1928), The Road to Mandalay (1926 in truncated and badly deteriorated form), and The BlackBird (1926). Hopefully, the release of The Unholy Three is a sign that the studio will release the remaining films of the strangest collaboration between director and actor in cinema history.

Among the new Lon Chaney DVD releases is the 1930 sound remake of The Unholy Three with Jack Conway directing Chaney and a mostly different cast. The only interest with the latter film is the novelty of hearing Chaney’s voice. As in the silent film, the actor took on various disguises, this time allowing 1930 audiences to potentially envision the famed “Man of a Thousand Faces” as, additionally, the “Man of a Thousand Voices.” It was not to be. Chaney died shortly after filming and the resulting one and only film to feature the actor’s voice does not bear that potential out. Chaney, dying of throat cancer, is horse throughout the film. To make matters worse, actor Harry Earles was far more magnetic and compelling in the silent film art form.His thick, German accented voice in the sound remake is an epic distraction.

Lon Chaney was understandably reluctant about making the transition to sound, his style of acting was so ingrained in silent film emoting. Knowing Browning to be equally uneasy with sound, Chaney unwisely requested the pedestrian Conway to direct. Under Conway, who had no feel or vision for the eccentric, the remaining cast in the sound remake are sanitized, hack versions of the far more eccentric and genuine cast in the Tod Browning directed silent film.

The original, silent Unholy Three (1925) catapulted Browning into star director status. Browning had languished for ten years as an assignment director who rarely had a feel for the mostly banal material handed him. The Unholy Three was different. It contains most of the elements we now associate as bearing Browning’s unique, personal stamp: The quandary of the social outcast combined with perverse characterizations and surreal plot. Before The Unholy Three, signs of Browning’s obsessions were already noticeable, if somewhat subdued, in his attraction to portrayals of criminal misfits, such as The Wicked Darling (1919-starring Browning favorite Priscilla Dean, with Chaney), Outside the Law (1920, also with Chaney), and White Tiger (1923-also with Dean). With The Unholy Three, Browning, working with writer Tod (Freaks-1932) Robbins, was finally able to craft a film which attractively resonated with the aberration of his soul.

Aptly, the film begins in a carnival setting. Already, Browning, who had run away from home to join the carnival, was in familiar territory. The Unholy Three consists of gang leader Professor Echo- the ventriloquist (Lon Chaney ), the spitfire midget Tweedledee (Harry Earles), and that marvelous mastodonic model of muscular masculinity, Hercules the strongman (a very young Victor McLagalen). An enticing girl, “who broke the Sultan’s thermometer”, bids patrons into the carousel of debauchery. While the three entertainment outcasts are performing, Echo’ s girlfriend, Rosie O’ Grady (Mae Busch) is picking pockets. It doesn’t take long for the bacchanal to turn helter-skelter. In the middle of the show, Tweedledee spies a young boy laughing at him and brutally kicks the lad in the mouth, splattering the boy’s shirt in blood. Eighty six years later, the scene is still unsettling. In a flurry, a brawl breaks out and Hercules amazingly pulls Tweedledee from harm’s way, but the local law enforcement arrives to shut the show down.

Fortunately, the Unholy Three have a side scam. A visually compelling scene shows the shadowed Chaney, huddled with his cohorts, planning the life of crime. Echo dons old lady drag as Grannie O- Grady. With Tweedledee, Hercules and “granddaughter” Rosie, the four open up a store front. It is a pet store which, on the surface, specializes in talking parrots, but behind the facade it’s rocks the four are mining.

Even the parrots are a gimmick. They cannot actually talk, but appear to when Echo, the ventriloquist (aka Grannie) throws his voice to make it appear as if the parrots are talking (amusingly, and a bit surreal, their voices are depicted in cartoon balloons). Once sold, the parrots lead the Unholy Three into the homes of diamond owning customers. Tweedledee, disguised as an infant in carriage, accompanies Grannie to help with the heist. Browning treats the outlandish plot with admirable seriousness. With Chaney, Browning also treats the drag persona with depth of feeling. Chaney never camps it up and delivers a remarkable, multifaceted performance. As powerful as Chaney is in the lead role, he damn near is eclipsed by his dwarf co-star Earles, who can give cigar chomping Little Caesar a run for his money. Tweedledee malevolently taunts and manipulates Hercules, threatens Rosie, and plots mutiny against Echo. Epic sleaze in such a small package impresses.

One of Earle’s best scenes is acerbic, tense and involves jewels heisted from a murdered victim along with a toy elephant. Rosie, oddly, falls in love with the geek pet store employee/potential fall guy Hector (Matt Moore). Busch and Moore genuinely convey trashiness (her) and nerdy (him) in comparison to their synthetic counterparts in the sound remake. McLaglen too projects a tawdry quality and has a run in with an ape which is almost hypnagogic.

A change of heart, sentimental transformation weakens the film somewhat, but Chaney convinces with astoundingly superior acting. Chaney deserves all the acting accolades he has received from film historians, buffs, and critics. While The Unholy Three is not, on the surface, as macabre as later Browning, Chaney films, it has retained its delirious edge well into the 21st century.

Tod Browning‘s frequent collaborator Waldemar Young wrote the screenplay for The

Mystic from Browning’s story, and it is clearly belongs with their family of work

together, which includes The Unholy Three (1925), The Blackbird (1926), The

Show 1927), The Unknown (1927), London After Midnight 1927), West

of Zanzibar (1928), and Where East is East (1929). The early knife-throwing act

seen here could be a blueprint for the same act in The Unknown. The

Mystic (1925) opens in a Hungarian gypsy carnival. The main attraction of

the carnival is “The Mystic,” Zara (Aileen Pringle). Zara is part of a trio,

which includes Poppa Zazarack (Mitchell Lewis) and Zara’s lover Anton (Robert

Ober). Of course, Zara’s clairvoyant act is all illusion and Browning, as

usual, lets his audience in on the trickery almost from the outset.

Conman Michale Nash (Conway Tearle) approaches the trio with a proposal to

take their act to America, where they can bilk naive, rich Manhattanites out of

their fortunes. The New Yorkers make Zara’s seances a hit, although not all of

the natives are so gullible, and the police are secretly investigating the

scam. To complicate matters, Nash puts the moves on Zara, and Anton is pushed

aside. Love does funny things, and soon Nash develops a conscience. He becomes

reluctant to swindle a young heiress. The ever-jealous Zara believes Nash must

want her for himself; but Nash simply wants to reform and make a better, honest

life for Zara. Their relationship is reminiscent of the one between Priscilla

Dean and Wheeler Oakman in Browning’s Outside The Law 1920), as are

the familiar Browning themes of reformation and unpunished crimes.

Pringle shows considerable screen charisma; or, at least, Browning draws it

out of her here. Her performance compares to other great female roles in

Browning’s ouevre: Joan Crawford in The Unknown and Lupe Velez in Where

East is East. In many scenes, such as the knife-throwing scene, Pringle

looks remarkably like Crawford; in close-ups, Pringle exudes the same soft

sensuality and subtle anguish. In other scenes, Pringle shares the bubbly

quality that we see later in Velez’s performance. At other times Pringle calls

to mind the mysterious exoticism of Edna Tichenor Unfortunately, Pringle and

Browning never got to work together again. The actress was reportedly difficult

to work with; most of her co-stars considered he an intellectual snob. Indeed,

she kept company with many of the artisans and intellectuals of her day. George

Gershwin and H.L. Mencken were among her notable lovers and she was married,

briefly, to author James M. Cain. Pringle’s acting career never really took

off, and she didn’t seem to care. She remained active in films (mostly small

parts, which included uncredited roles) up until the mid 1940s and died in 1989

at the age of 94.

Because of the lack of usual Browning stars, The Mystic is an

interesting, lesser-known film in the director’s canon. Not only is it

thematically related to his other films, but it also shows the idiosyncratic

continuity of his taste in actresses and his ability to mold actors, whoever

they were.

Note: the luxurious costumes for The Mystic were

the work of legendary French designer Erté. Erté, who was a

big fan of George Melies, said it was a thrilling experience to collaborate

with such a distinguished surrealist as Tod Browning.

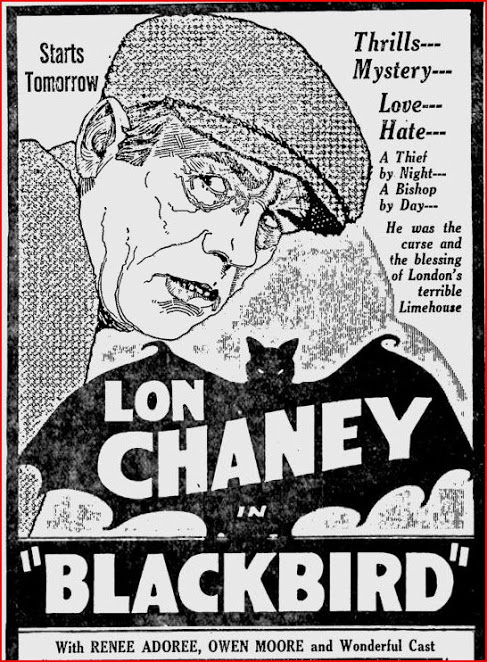

The Blackbird (1926) is a typically deranged underworld melodrama from the Tod Browning/Lon Chaney cannon. It has, lamentably, never been made available to the home video market, even though the restored print shown on TCM is in quite good condition and, surprisingly, is missing no footage. The Blackbird is also one of the most visually arresting of Browning’s films.

Browning opens the film authoritatively with close-ups of Limehouse derelicts fading in and out of the foggy London setting. Lon Chaney plays dual roles, of a sort. He is the debilitated cripple Bishop who runs a charitable mission in the squalid Limehouse district. Bishop’s twin brother is Dan Tate, better known as the vile thief The Blackbird. Actually, in this highly improbable (and typical, for Browning) scenario, Bishop and the Blackbird are one and the same. The Blackbird feigns the role of his own twin brother as a front, which means contorting his body as he acts as if he’s in excruciating pain (shades of Chaney, behind the scenes).

The Limehouse district unanimously loves the Bishop and dreads the Blackbird, save for the Blackbird’s ex-wife, Limehouse Polly (Doris Lloyd, the only one of the principals players who did not die young). Polly inexplicably still loves and believes in Dan. In a vignette, Browning does not hesitate to show the ugliness of the Blackbird’s racist side (an extreme rarity for the time), but the Blackbird has a slither of a soft spot himself for French patroness and music hall marionette performer Fifi (Renee Adore).

Dan is competing for Fifi’s attention with his partner in crime, West End Bertie (the amazingly prolific silent actor Owen Moore). At times, Bertie resembles a virile, monocled Bond villain. The suave Moore makes a worthwhile nemesis for the grimy Chaney. Unlike the Blackbird, Bertie is willing to convert from the dark side, for the love of a classy woman. Of course, this turn of events arouses jealousy and leads to intensified competition between the former partners, a frame-up job, and an ironic twist of fate when the two “brothers” will merge into a third, ill-fated persona.

The scenes of Chaney frantically changing identities with constables from Scotland Yard waiting below are deliriously incredible. The constables buy it, and so does an audience open to allowing the capered stream to wash over it.

Browning spins his elastic yarn a bit like Albert Finney’s Ed Bloom in Big Fish (2003). Aided enormously by Chaney’s energetic conviction, and with his penchant for a tenebrous, commanding climate, Browning pulls the ultimate con job on his audience. During its running time we are so drawn into the commanding perversity of Browning’s fable that the inherent haziness of the narrative’s essence rarely obscures his inclusive vision.

The Road to Mandalay (1926) & West of Zanzibar (1928) represent the Tod Browning/Lon Chaney collaboration at the height of its nefarious, Oedipal zenith, brought to you, for your entertainment, by Irving Thalberg.

Unfortunately, The Road to Mandalay exists only in fragmented and disintegrated state, a mere 36 minutes of its original seven reels. In this passionately pretentious film, which is not related to the Kipling poem, Chaney plays “dead-eyed” Singapore Joe (Chaney achieved the eye effect with egg white) who runs a Singapore brothel. Joe’s business associates are the black spiders of the Seven Seas: the Admiral Herrington (Owen Moore) and English Charlie Wing (Kamiyama Sojin), the best knife-thrower in the Orient. Joe’s relationship with his partners is tense and, often, threatening.

Apparently, Joe’s wife is long dead. The two had a daughter, Rosemary (Lois Moran), who Joe left at a convent in Mandalay, under the care of his brother, Fr. James (Henry Walthall). Joe, a repulsive sight, occasionally emerges from his sordid, underworld activities to visit Rosemary, who works in a bazaar. Joe plans to clean up his act within two years, once he has enough money to undergo plastic surgery and retire. Joe wants to be a reborn man, so he can reunite with his daughter and rescue her from the confines of poverty. Rosemary, however, unaware that Joe is her father (a frequent Browning theme), is repulsed by dead eyed Joe, understandably mistaking his friendliness for sexual predation. Fr. James warns Joe that waiting two years is too long. Joe’s insistence for patience only makes Fr. James skeptical that Joe can actually achieve or sustain the redemption necessary to give Rosemary a good life.

One day the Admiral walks into Rosemary’s Bazaar and discovers love at first sight when meeting Rosemary. Falling in love with his partner’s daughter inspires the Admiral to instantaneously see the light and put his past behind him. It is the Admiral, rather than Joe, who undergoes conversion. After spying Rosemary preparing for her impending wedding, Joe discovers the truth. He succumbs to an unsettling rivalry for his daughter and is furiously determined to put a stop to the union. Joe goes to Fr. James, insisting that the Admiral, like himself, is too defiled, too corrupt. The priest tires to assure Joe that the Admiral’s about face is genuine; he’s been converted by love. In a rage, Joe attempts to strangle his brother. A reel or so is missing here and next we find out that, somehow, Joe has shanghaied the wedding, kidnapped the Admiral, and is bound for the seven seas.

Searching for her missing lover, Rosemary arrives at Joe’s brothel, but she is lured upstairs by Charlie Wing. Joe arrives in time to stop Charlie from having his way with Rosemary, but the Admiral also arrives and a knife fight ensues, during which Rosemary stabs her father. Mortally wounded, Joe blocks Wing’s way and urges the Admiral to take Rosemary away to the seraphic life. Fr. James arrives in time to give Joe the last rites.

The Road to Mandalay is depraved, pop-Freudian, silent melodrama at its ripest. Fortunately, both Browning and Chaney approach this hodgepodge of silliness in dead earnest. Chaney is simultaneously cocky, parental, disturbingly coarse, and leering, projecting pathos and machismo. His Oedipal wailing, when his daughter tells Joe that she hates the mysterious father who has abandoned her, is classic. Browning, as was typical, idiosyncratically mixes melodramatic hi-jinks with exotic locales and strong actors. Unfortunately, The Road to Mandalay is in such dissipated state that it makes for burdensome, strained viewing. The only known print is a 16 mm abridged version, which was discovered in France in the 1980s. Even in its abridged state, The Road to Mandalay is intoxicating, outrageous silent cinema melodrama, badly in need of restoration.

West of Zanzibar (1928) is also missing footage, but, unlike The Road to Mandalay, it is in much more viewable state. Enough of the film remains intact,so as not to appear too fragmentary. Originally tilted Kongo, West of Zanzibar is the most flagrant, delightfully vile of the Browning/Chaney Oedipal absurdities.

Chaney plays Phroso. Phroso is married to Anna (Jacqueline Gadsden) and together they work in a Limehouse music hall as a magic act (in the early scenes as the magician, the protean Chaney gives a remarkable, Chaplin-like performance). Behind Phroso’s back, Anna is carrying on an affair with Crane (Lionel Barrymore). When Phroso and Crane inevitably fight over Anna, Phroso falls from a great height, forever crippling himself. After a short time has passed, Phroso is told that his wife has returned to town, with a baby, and is in the local church. The dead-legged Phroso zips down to the church via scooter and crawls into the tabernacle, only to find his wife, with crying babe in arms, collapsed in death, at the feet of a Madonna and child statue. Phroso looks at the baby girl, then at the Madonna, and vows revenge on Crane and the infant.

Twenty years later, Phroso re-emerges as “Dead Legs”: a witch doctor and trader, lording over a swamp in Africa, utilizing his cheap parlor tricks to keep the local cannibals in submission. Dead Legs is under the care of the derelict, alcoholic Doc (Warner Baxter) and an assortment of unsavory characters. Using the natives, Dead Legs steals ivory from his nemesis, Crane. It’s all part of a twenty year grand scheme for ultimate revenge.

Dead Legs summons Maisie (the beautiful, tragic, and short-lived Mary Nolan). Maisie is the now grown infant, whom Phroso believes to be the child of Anna and Crane. During the past twenty years, Maisie was placed, by Phroso, in the surroundings of a seedy bar in Zanzibar. Naturally, Maisie has become a tragic and loose alcoholic. In the original script, Maisie was placed in a brothel and raised as a debauched prostitute who contracts syphilis. However, producer Irving Thalberg predictably insisted this be softened somewhat in the film, which only lowers the film’s sleaze level from ten to about a nine and a half.

Dead Legs instructs the tribesmen to inform Crane that it is he, their master, who has been stealing the ivory. Of course, this kind of grimy silent era melodrama insists on throwing a monkey wrench or two into the scheme, complications Browning delivers in spades. Doc falls in love with Maisie and finds himself at odds with Dead Legs torturous treatment of the girl, who has recently sworn to kick the bottle. Nolan excels in the scene in which her paralyzed father descends from his wheel chair, slithering towards her. She is simultaneously petrified and optimistic, but Dead Legs drives her back to the brink of brandied insanity. Enter Crane, who sadistically reveals to Dead Legs the terrible secret that Maisie is Phroso’s daughter, not Crane’s.

It’s cornball, grotesque spectacle that Chaney and Browning treat as austere entertainment. Crane is shot and killed by the natives. It is tribal custom to burn alive a female relative of a dead male. The natives had previously been told that Maisie was the daughter of Crane and they demand that the sacrificial custom be carried out. Dead Legs must now make amends for his terrible mistake and hopes he has one last parlor trick up his sleeve to save his daughter and Doc.

As Dead Legs, Chaney delivers an amazing, masochistic, emotionally high-octane, and downright creepy performance. He writhes his way through most of the film, contorting his body with gleeful abandon. Chaney was a master of pantomime expression, learned from years of communicating with his deaf-mute parents. Chaney communicated best with those who shared his penchant for what others consider macabre. His wife had previously been married to a legless man and his preeminent director, Tod Browning, ran way from home to join the carnival, supposedly having had at least one affair with a freak. In many of his films, Browning depicted men paralyzed from the waist down, and later, in Freaks (1932), utilized actual legless freaks.

Together, Browning and Chaney acted out of the darkest recesses of their psyche in the silent era’s most manic productions, and they did it with authentic devotion.

The screenplay for The Show (1927) was written by frequent Tod

Browning collaborator Waldemer Young (with uncredited help from Browning). It

is (very loosely) based on Charles Tenney Jackson’s novel, “The Day of

Souls.” Originally titled “Cock O’ the Walk,” The Show is one of the

most bizarre productions to emerge from silent cinema, nearly on par with the

director’s The Unknown from the same year.

John Gilbert plays Cock Robin, theballyhoo man at the Palace of Illusions. A character with the name of an animalis a frequent Browning trademark, and Gilbert’s Robin is a proud Cock indeed,both the character and the actor. The Show amounted to punishment forstar Gilbert, who had made what turned out to be a fatal error. When co-star

and fiancee Greta Garbo failed to show up at their planned wedding, Gilbert was

left humiliated at the altar, where studio boss Louis B. Mayer made a loud

derogatory remark for all to hear. Gilbert responded by thrashing Mayer. Mayer

swore revenge, vowing to destroy Gilbert’s career, regardless of cost (at the

time Gilbert was the highest paid star in Hollywood). Mayer’s revenge began

here and climaxed with the coming of sound, when he reportedly had the actor’s

recorded dialogue manipulated to wreck Gilbert’s voice and career. Whether

Mayer’s tinkering with Gilbert’s voice is legendary or not, Mayer did

intentionally set out to give Gilbert increasingly unflattering roles, and the

consequences were devastating for Gilbert. Having fallen so far, so fast,

Gilbert took to excessive drink. He actually had a fine voice and starred in a

few sound films, including Tod Browning’s Fast Workers (1933) and with

Garbo in Queen Christina (1933) (she insisted on Gilbert, over Mayer’s

strenuous objections). Gilbert died forgotten at 37 in 1936, and became the

inspiration for the Norman Maine character in a Star is Born (1937). The

Show was the first film after Gilbert’s aborted wedding incident, and

instead of playing his usual role of swashbuckling matinee idol, Gilbert is

cast as a cocky lecher.

Cock Robin is the barker for a Hungarian carnival, dazzling the ladies and bilking them of their hard earned silver. He ushers patrons in to the show with the help of “The Living Hand ofCleopatra,” a disembodied hand akin to Thing from “The Addams Family.” AmongCock’s unholy trio of mutilated-below-the-waist attractions is ‘Zela, the Half

Lady.’ “Believe me boys, there are no cold feet here to bother you!” Zela is

followed by ‘Arachnadia! The Human Spider!,’ a heavily mascaraed, disembodied

head in a web (played by the enigmatic Edna Tichenor, Lon Chaney‘s nocturnal Goth companion Luna in London After Midnight and ‘Neptuna, Queen of the Mermaids!’ who inspires the divers to “go down deep!”

Next up in the Show is a reenactment of Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils. Browning ups the ante here well past Oscar Wilde. Cock disappears behind a door and re-emerges as the bearded John the Baptist. (This is another frequent Browning theme; a

Next up in the Show is a reenactment of Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils. Browning ups the ante here well past Oscar Wilde. Cock disappears behind a door and re-emerges as the bearded John the Baptist. (This is another frequent Browning theme; a

character, via a door, is transformed into a new character and transported into

a new world). Awaiting him is Salome (Renee Adoree, who became an instant sex

symbol when she starred with Gilbert in 1925′s the monster hit The Big

Parade—like Gilbert, Adoree tragically died in her mid thirties). Salome

demands the head of the Baptist from Herrod. Thanks to a trap door and fake

sword, the head of Cock’s Baptist is severed but still living, at least long

enough to react to the big wet kiss Salome plants on its lips.

Behind the act, Salome and Cock have a broken relationship. She is currently mistress to the nefarious and extremely jealous Greek Lionel Barrymore while Cock is attempting to latch onto Lena (Gertrude Short), the daughter of a wealthy shepherding merchant. The

Greek may have a jealous streak, but so does Salome, who shoves Spider Baby

Edna aside when she flirts with Cock, telling her “Away from him. You’re

freaks, not vampires!”

Cock gets blamed for the murder of Lena’s daddy after Salome tells Lena that he’s a hedonistic opportunist. The real murderer is none other than The Greek who, aware of the continued chemistry between Cock and Salome, plans to give Cock a disembodied head for real. In the arena of sexual resentment The Greek gets his comeuppance via the

animal kingdom (typical Browning theme number five, or six, if you’re still counting).

This time, the instrument of revenge is none other than a poisonous iguana in a

closet!

Unfortunately, The Show is flawed by a saccharine finale. Cock sees

the light of redemption through Salome and a selfless act. It may be high

cholesterol sentiment but it’s served up in the director’s unique, devious

style, with the principals finding nirvana in the only place they could in a

Tod Browning melodrama; on the carnival stage.

London After Midnight (1927) is the most sought after and discussed lost film of the silent era. Whether it actually deserves to be the most sought after has been intensely debated, but the fact that London After Midnight is lost is solely the fault of MGM.

MGM head Louis B. Mayer was something akin to the devil incarnate. For Mayer, film was strictly profitable, escapist fare to corn feed an increasingly dumb down audiences. At the opposite end of the spectrum was his in-house studio competitor, producer Irving Thalberg, who nurtured the Tod Brownings and Lon Chaneys of the world. Thalberg was hardly infallible (he sided with Mayer, against Erich von Stroheim’s 9-hour version of Greed [1925,] which resulted in the film being excised and led to an actual fistfight between Mayer and Stroheim). However, Thalberg’s concern was to make quality films, as he saw quality. Hardly the egoist, Thalberg never took a producer’s credit. He could turn out escapist family fare, but he was eclectic in his tastes and had a penchant for edgy, risk taking films with only the side of his eye on the profit meter.

Sometimes the devil wins, and when Thalberg died at the age of 37, Old Nick (Mayer) had no one to rein him in. MGM, under Mayer, had a notorious habit of buying out rivals—the original versions of the studio’s watered-down remakes—and then would make every attempt to destroy and/or suppress the superior original. For instance, they bought out the 1940 British version of Gaslight and unsuccessfully attempted to destroy all the copies just in time for the debut of their inferior 1944 version, starring Charles Boyer. MGM did destroy many, but not all, copies, and understandably earned the genuine resentment of the British film industry.

MGM did the same to Paramount’s superb, 1931 Academy Award winning Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde to make way for their laughably bad 1941 version. They were successful, or so they thought. For a number of years, it was believed all copies of the 1931 Hyde had been destroyed and it was therefore a lost film, until, may years later, copies resurfaced—much to MGM’s chagrin.

When Tod Browning wanted to remake his London After Midnight as Mark of the Vampire in 1935, MGM did not have to go on a search-and-destroy mission, since they owned the original. The studio saw no commercial value whatsoever in preserving a silent film, so the original was essentially buried to make way for the new version. Predictably, it fell into neglect until some thirty years later when the only remaining known copy was destroyed in a fire. It is entirely possible that MGM intentionally destroyed multiple copies of its own film, simply to make competitive room for the remake. Whether that remake is superior or inferior is pure speculation.

In 2003, Rick Schmidlin of Turner Classic Movies arduously produced a photo still reconstruction of London After Midnight. It is probably the only version of the film we, and future generations, will ever see. Even from a stills-only reproduction, it is clear that Midnight is the original American Goth Film. Chaney’s vampire, partly inspired by Werner Kruass’ Caligari, is a make-up artist’s delight, and an actor’s hell. Fishing wire looped around his blackened eye sockets, a set of painfully inserted, shark-like teeth producing a hideous grin, a ludicrous wig under a top hat, and white pancake makeup achieved Chaney’s kinky look. To add to the effect Chaney developed a misshapen, incongruous walk for the character. To his credit, Chaney’s crepuscular rogue looks as loathsome today as it did over eighty years ago (enough so for Henry Selik to pay the character a homage in The Nightmare Before Christmas).

The film, taken from Browning’s story “The Hypnotist,” is essentially a drawing room murder mystery, with a detective hiring actors to play vampires in order to smoke out the guilty party through sheer fright. As with most of Browning films, the plot is painstakingly preposterous, which will alienate contemporary audiences who religiously subscribe to ideas of hyper-realism. It is the spectral ambiance and erratic characterizations which stamp the film with Browning’s aberrant panache.

Chaney as the vampire and Edna Tichenor as Luna, the Bat Girl are the original creepy and kooky, mysterious and spooky duo. Chaney also plays the second role of the professor Edward C. Burke and in some of the stills he could pass for Ebenezer Scrooge.

Robert Bloch (writer, Psycho-1960) saw London After Midnight in his youth and wrote of a Browning oddity in the film; the sight of armadillos scurrying across the dilapidated castle floor. It is an image we do not see in the still restoration, but Browning would repeat this surreal bit in both Dracula (1931) and Mark of the Vampire.

The late William K. Everson, a reliable historian, saw both films and claimed that the 1935 remake was considerably superior. Critics of the period disagree with Everson, holding the 1927 film as the better of the two. London After Midnight received mixed reviews upon its release in 1927, but the majority of the reviews were positive. Of all the Browning/Chaney films, Midnight reaped the biggest box office.

In its current state, which is a remarkable, commendable effort on producer Schmidlin’s part, it still is virtually impossible to compare this with the remake. What is evident is that the earlier film’s production design, set in London as opposed to Prague in the remake, is superior; which is saying quite a bit since Vampire’s design is, in itself, handsomely mounted.

Midnight also has fewer characters, a more minimal murder plot, is silent (an art form both Browning and Chaney were far more comfortable in) and has Lon Chaney starring, which would seem to add up to a better, overall film.

In 1935, Browning requested to remake Midnight as Mark of the Vampire, starring Lionel Barrymore, Bela Lugosi, Lionel Atwill and Carol Borland. Browning’s status at MGM was sensitive at best, even though he was still under Thalberg’s protection. Neither Mayer nor the studio had forgiven Browning for Freaks (1932) and his salary for Mark was cut to half of its former amount, which he humbly accepted. Thalberg’s protective umbrella vanished when the producer died prematurely, shortly after the release of Browning’s The Devil Doll (1936).

After that film, Browning sat dormant for two years until he was able to direct Miracles for Sale (1939), an uneven film that featured yet another Browning depiction of below-the-waist mutilation. It was to be his last. He was unceremoniously fired by MGM producer Carey Wilson, whose early career Browning had greatly assisted. So much for loyalty.

For Mark of the Vampire, Browning worked with cinematographer James Wong Howe. Howe’s work in the film was praised, but Howe did not care for working with Browning, who he said “did not know one end of the camera from the other” (but, then, neither did Luis Bunuel). Browning, however, was a hard-driving perfectionist and took great care in the craft and design of the film; the expressionistic, winged descent of Borland is strikingly impressive.

Browning always grumbled about the finished state of his Dracula (1931). In his original edit, Dracula was ten minutes longer and was even more deliberately paced, with Lugosi’s count almost entirely invisible during the second half, which, according to Browning’s sensibilities, made perfect sense. The Count, as Browning’s “Living, Hypnotic Corpse” (an act the director played in his carnival circuit days ) pulls a disappearing act. But, Universal spoiled that by cutting several scenes and adding close-up shots of the vampire grimacing, much to Browning’s permanent dismay (he refused to ever watch the film again).

Browning got his way regarding the presence of the Count in Vampire. As in Terence Fisher’s Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1966) the vampire is mute and predominantly an unseen spirit. Lugosi is even more effective here with his reduced, minimal presence. He is made up to look like Dracula, but projects increased savagery in his silence, making for a highly effective, grinning demon that differs from Chaney’s look but emulates the former’s pantomime. Lugosi’s Count Mora also sports an unexplained bullet wound to the temple.

Unfortunately, Browning once again fell prey to unimaginative producers, who butchered Vampire by excising some twenty minutes, which is evident throughout this highly incoherent film. The result is something akin to a fascinatingly flawed, unintentional surrealist egg. In the original script, the Count and his daughter were incestuous lovers who committed suicide with bullets to the head, thereby incurring the curse of the vampire. Not surprisingly, that part of the story was cut, but Lugosi’s bleeding temple remained untouched, sans explanation. Borland is equally impressive. Her Luna tops the look of Tichenor’s, and her portrayal inspired Charles Addams’ Morticia.

Guy Endore (Werewolf of Paris) wrote the script from Browning’s story. Mark of the Vampire is saturated with sensational Gothic texture (which includes possums inhabiting the castle). The visceral editing somehow add to the film’s appeal, even if it is a bit too talkative, bogged down with moments of forced comedy relief and Lionel Barrymore’s on-the-sleeve acting (although sometimes he seems more villainous than the vampires, which is beneficial to the overall milieu). Vampire adds up to an outrageous, hallucinatory film with genuinely perverse personality and a surreal, ominous style, far more so than the average Universal genre potboilers.

When released, critics generally praised the film, but many complained about the “trick” ending, which is stupefying since it is hinted at fairly early on. Plus, it has the same ending and story as Midnight, which was a huge box office hit only eight years before. Perhaps critics from the period all suffered from long term memory loss. The ending actually makes the film, giving a facetious, Addams family-like sheen to the proceeding austerity.

Browning ended his collaboration with Lugosi with this film. Their work together started with The Thirteenth Chair (1929) when the director was scouting around for Dracula (despite rumors, Chaney was not set to be cast as the Count and there is no evidence that he would have been, even if he had lived, although Chaney would have been an obvious choice to consider).

Browning’s long term association with Barrymore would come to an end in the following year’s The Devil Doll. It was also the beginning of the end for Browning’s unparalleled brand of artistry.

The Unknown (1927) is one of the final masterpieces of the silent film era. Suspend disbelief and step into the carnival of the absurd. The Unknown is the ebony carousel of theTod Browning/Lon Chaney oeuvre, the one film in which the artists’ obsessions perfectly crystallized. This is a film uniquely of its creators’ time, place and psychosis and, therefore, it is an entirely idiosyncratic work of art, which has never been remotely mimicked, nor could it be. That it was made at MGM borders on the miraculous, or the delightfully ridiculous, but then this was an era of exploratory boundaries, even at the big studios (again, the risk-taking Irving Thalberg produced).

“There is a story they tell in old Madrid. The story, they say is true.” So opens the tale of “Alonzo, the Armless.” Browning spins his yarn like a seasoned barker at the Big Top of a gypsy circus where “the Sensation of Sensations! The Wonder of Wonders!,” Alonzo (Lon Chaney), the Armless, throws knives, with his feet, at the object of his secret affection, Nanon (an 18 year old Joan Crawford).

Illusions abound. Alonzo is actually a double-thumbed killer on the lam. With the aid of a straight jacket and midget assistant Cojo (John George, who worked with Browning in Outside the Law 1920), Alonzo feigns his handicap and performs the facade of one mutilated.

In addition to evading the law and securing employment, Alonzo’s act of the armless wonder benefits him greatly. Nanon has a hysterical, obsessive repulsion to the very touch of a man’s arms. She calls on the Almighty to take away the accursed hands of all men. Nanon vents histrionic, sexual anxiety to Alonzo every time Malabar the Mighty (Norman Kerry) puts his vile hands upon her. Alonzo, ever the performer, simulates expressed sympathy, although his affection for Nanon is the one thing about Alonzo that is genuine.

Alonzo, secretly venting enmity, advises Malabar on how to win Nanon. It is, of course, intentional ill-advice which will eventually karmically rebound and become genuine ill-advice for Alonzo. Malabar’s arms are muscled and strong, compared to Alonzo’s armless torso, or compared to Alonzo’s deformed, hidden double thumb—the very same double thumb which he used to strangle the ringmaster of Browning’s perverse milieu: Nanon’s sadistic father, Antonio Zanzi (Nick Ruiz, hinted at being the abusive source for Nanon’s hatred of a man’s touch).

After Alonzo swears to care for her, Nanon embraces him, to the alarm of Cojo. The loyal Cojo fears that Nanon will discover Alonzo’s secret. But, Alonzo must have, marry, and own Nanon, despite the fact that she hates the hands of all men, and would certainly hate the hands of the double-thumbed murderer.

An alluring shot of Crawford, filmed through gauze, gives way to a mesmerizing, humorous scene of Alonzo lighting his cigarette with his feet, long after removal of the binding straight jacket beneath his coat (shades of Freaks-1932-to come). Cojo laughs at the irony. Alonzo is perplexed. “Look, Alonzo, you are forgetting that you have arms!” Aghast, Alonzo looks at the cigarette between his toes and the freed, cursed hands which keep him from possessing Nanon. Repulsed, Alonzo clutches the arms of the chair. The revelation of his dilemma provokes a flow of maddening tears, which evolves into abject horror and gives him the terrifying answer: a a martyrdom of emasculation, all for unrequited love. “Not that, Alonzo!” Chaney’s intense concentration obliterates all doubts. If we were not terrified, we would laugh insanely with him.

Alonzo goes to see the underworld surgeon. When the doctor inquires into Alonzo’s desire, Alonzo pantomimes a slash across his shoulder. This is an amazingly acted, unsettling scene in which Chaney’s simple pantomime slash solicits genuine shock and shudder.

After a long recuperation, Alonzo goes to see Nanon, who is astonished at his withered appearance, which he explains away as the result of having “lost some flesh.” Chaney’s meltdown scene has been much written about. Burt Lancaster listed it as the greatest acting scene in all of cinema. Chaney expresses A teary-eyed gleam, wistful yearning, brooding, barely concealed jealousy, tragedy, hysterics, and fatigued collapse from the masochistic futility of his sacrificial mutilation all within a matter of seconds.

Forced to perform yet again, Alonzo must mask his true reaction as Nanon kisses hands that she no longer fears. Nanon unwittingly mocks Alonzo’s sacrificial maiming. Despite Alonzo’s web of lies, his facade, his cruel betrayal of Cojo and maliciously plotting ghastly revenge, Chaney has our unmitigated sympathy. Chaney makes us understand and root for the misunderstood. God bless the freaks. It is only fitting that Chaney, the quintessential performer, climaxes as the performer pathological.

And only Tod Browning could have directed this lurid, deliriously surreal pulp melodrama/debauched fairy tale without batting an eyelash once. Browning’s sincerity is contagious and spellbinding during the film’s brief 50 minute running time, which ends with a startling, ferociously driven, symbolic finale.

For many years The Unknown was thought lost. All but 15 minutes of the film have been recovered, which may give a glimmer of hope for those awaiting the discovery of the infamous London After Midnight.

Browning essentially kept remaking the same film. He was a peculiarity in Hollywood. He refused an agent, generally refused assignment scripts and, instead, consistently sought out material that interested him.

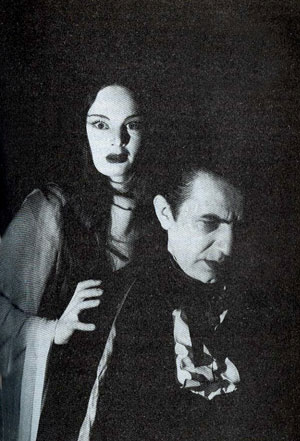

Where East is East (1929) was the last of the Tod Browning/Lon Chaney collaborations, it was the last of Browning’s silent films, and it contained many themes from their previous efforts together.

The heavily scarred, large-feline-monikered Tiger Haynes (Chaney) is an animal trapper who has an uncomfortably playful relationship with his daughter Toya (the bubbly Lupe Velez). Their relationship alters between games of feline patty cake and overt protection. Daddy and Toya’s relationship gets thrown its first monkey wrench when Toya acquires a new boyfriend, Bobby (Lloyd Hughes).

Acting like a jealous lover, Tiger refuses to warm up to Bobby, until Bobby assists Tiger in saving Toya from a real tiger. Now Bobby is a real swell and welcome to the pride. While delivering tigers on a cruise to the East, Tiger and Bobby run into Tiger’s ex-wife and Toya’s mother, Mme. de Sylva (Estelle Taylor, the real-life one time wife of Jack Dempsey). For Bobby, Sylva is the embodiment of oriental fantasy. She is a true tigress with a jealous, soothsayer-like female servant (hints of a lesbian relationship). Sylva spews her man-baiting poison on the intoxicated Bobby, in order to exact sexual revenge on Tiger and parental revenge on their daughter,Toya. This is a reversal of West of Zanzibar (1928), in which Chaney was the parent exacting parental revenge on a whelp. The incestuous relationship hinted between Tiger and Toya (on Tiger’s part, twice unrequited) is paralleled in Bobby and Sylva.

Sylva enters Toya’s world and repressed, invisible secrets threaten the illusory fabric of Tiger’s world. Of course, some animals devour their young, and Sylva, one step removed, attempts to incestuously devour Toya. Unfortunately for Sylva, behind a fragile cage she has a nemesis in a gorilla holding a grudge for secret, past abuses. It is the savage animal kingdom that will exact revenge. Chaney, impotently declawed, scowls and threatens Sylva from the sidelines until he unleashes the beast, which will end in paternal sacrifice for the daughter he cannot possess (shades of West again).

Where East is East hands the film to Taylor, who, reportedly, managed her off-screen relations with men in a fashion similar to Sylva. Luckily, Taylor is up to the part, as is Velez, who conveys innocence, diverse emotions, and energetic sexual charm. Chaney is excellent as usual, in the secondary, castrated role.

One off-screen note of interest: “Mexican Spitfire” Velez and Taylor became quite close after working together in this film. Velez, pregnant and abandoned, spent her last hours on earth with Taylor, before departing her mortal coil with the aid of Seconal. Somehow, in the Browning universe, that is an apt, dark underside to the narrative.

Needless to say, Where East is East does not subscribe to any sort of orthodox realism. It is representative of the blue collar surrealism that both Browning and Chaney espoused and can be best enjoyed with a heaping plate of elephant ears and cotton candy, along with a well-worn copy of “The Interpretation of Dreams.”

The Thirteenth Chair (1929) is a real curio and Browning’s first sound film. Like a lot of early sound films, it is bogged down with that wax museum-like staging. This is yet another drawing room murder mystery, taken from an antiquated stage play, but being a Tod Browning production, the film cannot resist its own latent, deviant infrastructure in the acutely bizarre casting of Bela Lugosi as the well-dressed Inspector Delzante.

In the original play, the character of the inspector had a different name and was played for laughs. The Thirteenth Chair was an all around testing of the waters type of film, namely, in handling that new invention called sound, which neither Browning nor the production team were comfortably with (all too clearly). However, the main testing was the upcoming role of Dracula and for that reason Browning grabbed Lugosi, who had made the role a mega hit on the stage circuit.

Lugosi’s make-up, with sharply accented eyebrows, is patterned after the make-up he wore as Dracula in the play. His mannerisms are pure vamp, not at all what the role of the inspector originally called for. His first appearance is shot from the back. He is in a police station, dressed from head to shoes in white, but when he turns towards the camera, he delivers the lines as only a Transylvania Count would. Thankfully, Lugosi is wildly disproportionate to the role and serves as an almost surreal red herring to the film. This may have been a test project for Browning, but he had to make it interesting for himself and he did so first with his eccentric casting of the “Living, Hypnotic Corpse” as the inspector.

Lugosi beautifully mangles the English language, as per the norm, but his handling of the foreign tongue is much faster clipped than it would be in the 1931 Dracula, which gives lie to the ridiculously uninformed rumor that he learned his lines phonetically. Lugosi had lived in the states and performed the part for years before the film version so the actor’s delivery for Dracula was a directorial choice, as Lugosi indicated in interviews.

Lugosi has some wonderful, if eccentric bits. In one scene, Madame Rosalie La Grange (Margaret Wycherly) asks Delzante to speak plainly. The Inspector angrily responds, “Madame, I am ssspeaking purrrfactly klaaare!” In another bizarrely fascinating scene the Inspector is questioning the names of suspects from a murder committed during a seance. One woman tells him, “Helen.”A few seconds later, a second woman tells him “Helen.” Lugosi is taken back and then delivers a priceless spiel, “Halan. I see. Halan. Halan. Ssssooo, there are twooo Halans. Twooo Halans.” He walks over to the Madame, “Sssooo there were twooo Halans. An extraaa Halan. The name you were afraid to speak was Halan.” Itsssh tooo Klaaare.”

Browning’s work with Lugosi traces an interesting development through the three films they collaborated on. Here, the casting of Lugosi amounts to a deception. Lugosi as Delzante intentionally throws the film off into bizarrely wayward areas. In their next film, Browning’s Dracula often amounts to a parlor trick. Lugosi as Dracula ascends the stairwell. Renfield follows and sees, to his astonishment, that the Count has magically “walked” through a cobweb without disturbing the web itself. Dracula, like a leering magician, grins diabolically, issuing an disconcerting “come forth.” The collaboration climaxed in Mark of the Vampire (1935). In that, Lugosi is half of the quintessential, crepuscular goth couple (and an incestuous one at that). However, it is merely an elaborate hoax. One suspects Mark was Dracula as Browning intended.

The Thirteenth Chair is replete with eccentric dialogue, delightfully of its time, “So that’s the bee in your bonnet!” says the bland protagonist to his love. John Davidson is more interesting as the doomed Wales. Davidson competes with Lugosi in undead-like delivery. Unfortunately, Davidson gets offed too early in the film, but not before some entertaining eye rolling. Wycherly as the honestly fake spiritualist reprises the role she played on Broadway. Wycherly could be the catalyst for a Browning self-portrait. She is the grand deceiver who eventually lets the audience in on the deception. Browning would repeat this theme in his apt curtain call, Miracles For Sale (1939).

Serious awkwardness mars this film, a product from that transitional period from silent to the new, imposing medium of sound. Because of that awkwardness The Thirteenth Chair is not Browning in best form, but he still manages to make it a curiously personal, queer con. Two murders, one committed with all the lights out, a phony medium, a series of séances, a mysterious manor, stolen love letters, and potential blackmail all add up to standard Browning fare, with an extra oddity or two, two Helens that is.

Tod Browning’s Dracula is often unfairly compared to Murnau’s unauthorized Nosferatu, and it is an unfair comparison because the two are very different films, which merely happen to share the same literary inspiration. (Neither are mere adaptations. The only film to fairly compare to Murnau’s would be Herzog’s remake with Kinski and, indeed, it compares very favorably). The vampire of Murnau and Schreck is an accursed, repulsive animal, the carrier of a dreaded plague and the beast fights fiercely to sustain it’s life, like a rodent in it’s death throes. The Dracula of Browning and Lugosi is an outsider, a mesmerizing and intensely austere intruder, who comes to nourish on the aristocratic London Society, who he, paradoxically, yearns to to join (fittingly, for a genuine outsider, it is to no avail of course; he makes rather pronounced overtures and goes to extraordinary lengths to fulfill his ambition there).

Dwight Frye’s pre-bitten Renfield is nearly as strange an outcast as he is after his transformation, albeit in a far different light. Renfield is a bizarre, urban effeminate in an old meat, potatoes and superstition land. The villagers are outcasts too, but among them, Renfield is the doomed jester, misguidedly blinded by his foolhardy feeling of superiority over them and stubbornly oblivious to the peasants’ warnings.

The introduction to the inhabitants of Castle Dracula is among the most discussed in the annuls of Universal Horror and, to many viewers,it is also most perplexing. This is quintessential Browning. The static silence is punctuated with genuine dread, surreal humor, and the unnerving whimpers of a opossum. Karl Freund’s camera pans over a decidedly unreal set. The vampire brides slowly emerge as a bee scampers out of it’s little coffin. An opossum seems to be ducking for cover in it’s dilapidated coffin and it’s cries are the only living sounds we hear as we are introduced to Lugosi’s Count staring directly at the camera.

Renfield’s journey to Castle Dracula perfectly captures the sensory view of a crepuscular world. Indeed, no other Universal horror film would convey it as vividly and attempts to do so in later films proved pale imitations.

Renfield’s arrival to the castle, and state of confusion, is juxtaposed against the awkward but pertinacious emergence of Dracula. Lugosi’s emergence seems to partake of a genuine struggle and this echoes the delivery of his greeting which follows. This emergence sharply contrasts with the startling and confused appearance of armadillos scurrying in the ruins below, which also heightens Renfield’s confused state.

Critics have unfavorably compared this scene to Melford’s much more fluid shot of Villar’s Count appearance atop the stairwell in Dracula (The Spanish Version). This can be dismissed as sloppy, revisionist criticism. Browning is a master at those elongated pauses where little seems to be happening. With careful, focused attention, this proves to be deceptive, but admittedly is a struggle for viewers corn fed on television bred aesthetics. Comparing the two is akin to comparing an artist as opposed to a mere craftsman. Melford’s scene is surface dramatics and cannot illicit anything remotely comparable to the surreal queasiness Browning evokes here. Additionally, Melford’s entrance climaxes with a jerky and unintentionally comic Villar greeting his visitor. With Melford, the effect is ruined, never recovers,and only worsens. With Browning, the unreal dread has just begun.

The vampire’s lethargic descent, set against the massive sets, resembles the pronounced, surreal fire and ice quality of an El Greco. Dracula’s torpid greeting to Renfield is an unnatural extension of his body movements, and is exactly how we might expect such a greeting to be delivered after a hibernating state.

The absurd myth that Lugosi learned his lines phonetically probably sprang from his verbal introduction here. We sense, not that Dracula is struggling to speak English, but that he is struggling to speak at all here. Lugosi had been in the states for five years and had been playing the part of Dracula on Broadway for three, so in 1931 his English was already as good as it would ever be. His English in Browning’s previous “The Thirteenth Chair”, while still not expert, was actually “better” than it was in Dracula. Lugosi himself discussed how intensely Browning directed his acting in the film, stating that the direction was very different than the way he had played the part on Broadway. Thus, the abnormal delivery was quite intentional on the director’s part and the actor never repeated the stylized performance, even when he played the role again some 17 years later in Abbott and Costello meet Frankenstein.

Browning, understandably, was an actor’s director. He had acted himself in some 50 films early in his cinematic career. While it’s true that he never found a real replacement for his beloved Lon Chaney, he did have a rewarding collaborative partnership with both Lugosi and Lionel Barrymore, even if he did not find those as satisfying. (He reportedly worked well with Lugosi, but only used him once more, in Mark of the Vampire. Browning’s relationship with Barrymore, by most accounts, proved to be combative but he did work twice more with Lionel in Mark and The Devil Doll , and, to be fair, the teaming of Chaney and Browning would not be equaled again until Herzog and Kinski).

Browning makes much use of body language with Lugosi, Van Sloan and Chandler. With Lugosi and Van Sloan he focuses intense concentration on the eyes and hands. When Dracula leers at the seated Renfield, Browning and Freund utilized a pinpoint spotlight in Lugosi’s eyes to enhance the hypnotic effect. It’s quite unreal and, just as equally effective, later there will be a symbolic connection to Van Sloan’s hyper-pronounced glasses.

The emergence of Dracula’s three brides, in an attempt to feast on the drugged Renfield, will also have a symbolic connection. Renfield will soon be transformed, but it will not be by the three women. Dracula stops them just in time to take over the feasting himself, and one wonders whether Renfield symbolizes the first of Dracula’s three replacement brides (Dracula tells Renfield earlier that he is only taking three boxes and one assumes, at first, that his brides will be traveling with him, yet they never re-appear and so this seems to be a set-up for their replacements. Had Renfield been as fiercely loyal a disciple as he professed he was going to be, he may have been converted to full fledged vampire and joined his master).

Renfield paves the way for Dracula’s entrance into society, a bit like the Baptist proclaiming that good news is coming. Like any disciple, Renfield is, by turns, both overly zealous in his proselytizing and frequently faltering in his loyalty and one feels it is the characterization of Renfield that Browning identifies with and enjoys the most.

Before merging with London society, Dracula must feed, and it is an innocent and waif-like flower girl that becomes his first victim. (The girl being of obvious lower class, he does not transform her, but merely kills her. London’s elitist status quo system quickly rubs off on him). Dracula is both elegant and sinister here.

Dracula enters the opera house to strains of Schubert’s “Unfinished” symphony and then, very quickly, the conclusion of Wagner’s “Die Meistersinger’ prelude. It is the only music in the context of the film. Browning’s extensive use of silence proved to be an artistically sound decision. That point was especially made when Universal tacked on Philip Glass’ execrable score for the film’s anniversary release.

We are now introduced to Helen Chandler’s complex and vastly underrated Mina. Again, Browning is expert in drawing forth a nuanced and interesting performance from an actor. The role of Mina is one of the most pointed criticisms in the Browning film, deemed unworthy and pale next to Lupita Tovar’s role of Eva in Melford’s version. Indeed, Tovar gives the only decent performance in the Melford film, but compared to Chandler, Tovar is obvious (yes, she’s more overtly sexual) and also more amateurish. Chandler acts with her body, her eyes, and facial gestures. The way Chandler touches herself, as she frequently does in the film, so delicately brushing her collar bone, as if to cover her vulnerably exposed flesh, conveys a sort of girlish outrage at Lucy’s expressed attraction to the dark toned utterances of their foreign visitor. Chandler’s is a beautifully and subtly nuanced performance which improves as her character evolves. The character of Mina evolves more than any other throughout the film. Mina’s bedroom scene with Lucy, further enhances this. As Mina listens to Lucy’s fascination with the Count, she again touches herself, folds her hands, looks intensely at Lucy with a young woman’s superficial naïveté and genuine concern. She runs her fingers over the wooden arm of the chair, a state of occupied wandering, as if it is a diversion from the true extent of her friend’s dark sexual attraction to Dracula. “Give me someone a little more normal,” Chandler says, acutely capturing her character’s Victorian stuffiness and adolescence. Chandler finally relents to Lucy’s crush. She gets up, still half mocking Lucy, covers her exposed flesh again, indicating her virginal state,and beautifully kicks up her knee in departure, like a sixteen year old girl.

Chandler’s years of acting experience are in full flower here. She had been very active in theater for well over ten years, had acted with both Barrymores in productions of Shakespeare and Ibsen, had gotten good reviews for the film Outward Bound and was already deep in the throes of the alcoholism that would eventually take her. She was hardly endowed with the innocence she portrayed in Mina, but undoubtedly tapped into the memory of it (and later, innocence lost) to give Mina resonance.

Lucy’s death scene is well filmed and shows Browning at the peak of his powers. A lamp with three female figures rests next to her (the figures echoing Dracula’s three vampire brides). Behind the lamp is an ominous clock. She drifts to sleep ever so slowly. Dracula first appears as a silent bat hovering before Lucy’s open window, then a moment later he is in human form, a few feet away from her as she sleeps. He methodically bends his arm, as if he is re-shaping from bat to human before he approaches her, moving as if almost under water. When he is inches away from her, the scene dissolves into a medical theater of sorts. Doctors are hovering over Lucy’s corpse as students watch from above. The students seem as lifeless as Lucy and not only do we have the feeling of undead, but a dream-like feeling of something unreal permeates the scene, as if sprouted from Baudelaire’s Poe.

We are now introduced to Edward Van Sloan’s Van Helsing. From the outset, he is a parallel figure to Dracula and, at times, seems just as sinister. His hand movements, when he touches Renfield’s hand for instance, recall Dracula’s distinct hand gestures. The exaggerated glasses, as stated above, have as much meaning as the pinpoint spotlight in Dracula’s hypnotic eyes. Both Dracula and Van Helsing can see well beyond the confines of their surroundings. They are the only two who actually see, the others are, metaphorically, like lost sheep attempting to see through a glass darkly.

Dracula and Van Helsing are metaphorically Christ and Anti-Christ although the distinction between the two is intentionally blurred. The comparison is apt, as this is the most religious of Universal’s horror films.

The much maligned second half of the film shifts perspective, but still does not resemble a real world at all and casts an aquatic spell over the receptive viewer.

Another very well filmed scene is the vignette of Renfield in his cell as his master silently pays call outside. The scene cross cuts between the tense, nerve-frayed, overtly emotional, pleading Renfield and the ice cold vampire; fire and ice again. Renfield bows his head, devastated, in a half prayer for the intended victim, Mina, which goes unanswered. This flows into Mina sleeping in her bed. Again Dracula appears as a bat hovering before a window. Then, Browning’s sharp trademark intercut. Dracula is suddenly in the room. He is in human form, but his arm is lifted, almost as if he is unfolding. Lucy’s three figure lamp is now mysteriously placed in Mina’s room. There is no explanation for this, save for symbolic foreboding. Another sharp intercut; a close-up of Lugosi, who looks young and even handsome here. A long shot of Draculas’ full, slowly approaching figure cross cuts with a repeated image of the sleeping Mina, then another sharp intercut to an intense close-up of Lugosi, whose face is now twisted into a hideous expression.

The following night reveals a Mina recounting her bad dream to fiancee Harker. Van Helsing overhears this, approaches her, puts on his glasses to examine her, lifts the scarf from her neck, to which she responds with an almost sensual gasp. This is Mina on the verge of transforming into a more ethereal and more interesting character who understandably begins to find her fiancee increasingly dull. Mina’s facial expressions range from introverted guilt, shame, half-masked pride, and finally, a thinly masked yearning for Dracula after he makes his appearance to the group. Van Helsing interrupts the foreplay between Mina and Dracula, and Mina reverts back, albeit briefly, to a more fragile, wounded state. But Mina’s is a wildly mercurial state and again she shifts, this time chastising the doctor after advises that she go to her room.

Dracula feigns concern over Mina’s bad dreams, while Mina twirls her fingers through her scarf. She rises her from the couch, kicks up her knee and closes her eyes in a state of ecstasy as Dracula recommends she do as the doctor advises. This is when the Puritan Van Helsing makes his discovery of Dracula in the mirror. The reactions to the smashing of the mirror are priceless. Herbert Bunston’s expression of uncomfortable awkwardness during Dracula’s explanation plays well with Manners’ display of disgust and Van Sloan’s gleeful pride.

Another highly effective bit of acting is in the scene in which Renfield describes his master, parting a red mist. This is Dwight Frye’s best scene in the film and he plays it with all the sincerity of an obsessed apostle. Renfield’s narration here resembles an epitaph for a biblical saint and his miracles.

The showdown between Van Helsing and Dracula, both believing themselves to be the protagonist, is made the more surreal by Dracula’s hissed departure, fleeing the cross, yet unaccompanied by any dramatic music attempting to tell us this is a dramatic scene.

The rest of the film primarily belongs to Chandler and one of the most unsettling images in that last quarter is the close-up of Chandler, almost fully vampiric, as she leans into Harker. Her wonderfully expressive eyes now express only deadness, a bit like a doll’s eyes.

Dracula descending down the stairs of Carfax Abbey to kill Renfield takes us back to Dracula descending down the stairs to greet Renfield near the film’s opening, and there remains but one act of penance to pay, this being from the film’s blasphemer, Count Dracula. When Van Helsing stakes him off screen, Chandler’s body twists, thrusting in agonized reaction, her firsts clench and her breasts heave as she loses her master and, we empathize because we will see nothing of the like again. Comparatively, recent pickings from the crop seem typical shallow fare. Browning’s Dracula is the real thing.

There used to be a theory in art college that many of the professors blandly bandied about like religious dogma. It was the theory of “aesthetics only.” This theory maintained that it did not matter whether a painting was of a landscape, a penis, or non-representational. A work of art could only be judged by aesthetic criteria.

The biggest problem with that theory is that it rarely holds true. A good example of this would be in comparing the work of Diego Riveria to the work of his wife, Frida Kahlo. Riveria was clearly a better painter aesthetically. He had a far better sense of composition, and a keener sense of color than Kahlo. However, Riveria lacked Kahlo’s obsessive vision, and it is her vision that remains far more memorably etched in our conscience.

Another example which blows the “aesthetics only” theory out of the water would be in comparing D.W. Griffith to his one-time assistant Tod Browning. There is no doubt that, aesthetically, Griffith was a far more innovative and fluid director. However, Griffith lacked two important qualities which Browning had in spades; obsessive vision and pronounced human empathy. It is the latter of these two vivid Browning qualities that renders Griffith a grossly inferior artist when compared to the inimitable Tod Browning.

Browning was consistently drawn to and connected with the social outcast, while Griffith espoused his racial superiority and reprehensibly tidied that up in his protruding “aesthetics” chest. That Griffith was ( and still is) celebrated, smacks of American and Hollywood hypocrisy and superficiality at its most blatant.

Of course, this is nothing new, nor is it confined to the film community. Conductor Rafael Kubelik was mercilessly attacked and driven out of Chicago by Tribune critic Claudia Cassidy because he programmed ethnic and contemporary music. How is the late Ms. Cassidy remembered? Chicago named a theater after her.

Celebrated New York Times Music critic Olin Downes publicly ridiculed Dimitri Mitropoulos for his not so secret sexual preference. The freak Dimitri left the New York Philharmonic and succumbed to a fatal heart attack shortly after.

Browning remains yet another outcast artist, who is critically compared in unfavorable standing next to the likes of Griffith and fellow “horror” director James Whale. Yet, Tod Browning defines the word auteur far more than these, or any director of his time, and he has had a far more impactful influence on the generation of auteur directors who followed him (including David Lynch, David Cronenberg, John Waters, Alejandro Jodorowsky, and Tim Burton[well, early Tim Burton]).

After the 1931 box office success of Browning’s Dracula and Whale’s Frankenstein, MGM second in command Irving Thalberg approached Browning and asked him to come up with something to outdo both of those films. Browning responded with his manifesto, Freaks.

From the beginning of Freaks‘ genesis, there were problems aplenty. Thalberg’s fascistic boss, Louis B. Mayer, was vehemently opposed to it even at the conceptual stage, and his objections only intensified. During filming, many on the MGM lot found the sight of the freaks so disturbing that they sought to have the production stopped. Fortunately, Thalberg came to Browning’s aid and saved filming from being sabotaged on numerous occasions.

Then there is Thalberg himself, who remains one of Hollywood’s most interesting paradoxes. Unlike Mayer, Thalberg loved movies and knowing his bad heart would doom him to an early grave, he worked diligently on projects he believed in, securing his legacy, albeit anonymously since he always refused screen credit. The Marx Brothers were a pet project. The brothers really did create as much surreal havoc off-screen as they did on and many at MGM wanted them gone, but Thalberg took them under his wing and lavished their productions with so much professionalism, craftsmanship and care that the Marx Brothers films following Thalberg’s death are substantially weaker.

As much as Thalberg loved movies, he loved them for their entertainment value alone and he had no understanding of film as art. It was Thalberg, with Mayer, who butchered Stroheim’s Greed. When Browning finished Freaks, Thalberg, who had previously defended Browning, did not hesitate to cut nearly a half hour of footage from the film (and, as was the norm at that time, burned the excised footage).