Coming out of the Warner Brothers cartoon factory, Ralph Bakshi emerged as one of America’s unheralded surrealists. He is as authentic in his way as Ken Rusell was. Both share a related aesthetic, which is closely linked to avant-garde cinema tradition, but grounded in the stylistic tenets of Surrealism. Russell, unquestionably flamboyant, probably has the more secured reputation with aficionados, while Bakshi too often is summarily dismissed as a cult animation specialist. Yet, as Paul Klee, Max Ernst, and Luis Bunuel have proven aesthetically more consistent (and infinitely more interesting) than that hero of male teenage angst, Savlador Dali, so too Bakshi likewise may come to be seen as the part of the pulse of Western Surrealism.

Bakshi’s debut, Fritz the Cat (1972), is delightfully of its period and could probably only have been made in the 1970s (although work on it actually began in 1969). It was a first on numerous fronts: The first X-Rated cartoon, Bakshi’s first feature (his previous work include a number of shorts and the television cult classic animated “Spiderman” 1967-1970), and the first cinematic adaptation of the work of Robert Crumb. Crumb himself thought Bakshi’s adaptation too subdued and hated it (it does lack the original’s bite), as did the cartoonist’s loyal fan base. Critics were divided over it then, and they’re still split on it, which sets the pattern for the whole of Bakshi’s work.

The critics of Fritz The Cat accuse it of blatant racism and sexism. Its defenders proclaim it as brutally honest and immune to political correctness. However, few dispute that Bakshi’s animation style is a highly original, handsomely mounted one.

It is set in the late 60s, as we follow the pot smoking, Candide-like protagonist Fritz out of college, into a Harlem ghetto filled with barroom brawls, riots, unbridled sexual escapades, drug abuse (which includes a heroin addled rabbit), cynicism, graphic anti-establishment violence (the police are literally portrayed as inept pigs), and revolutionary spirit.

Despite budgetary limitations and Crumb’s refusal to endorse the film, Fritz The Cat proved a success, even inspiring a sequel—The Nine Lives Of Fritz The Cat ( 1974)—which Bakshi was not associated with. Predictably, the sequel flopped, making the original look like a masterpiece.

Heavy Traffic (1973) is Bakshi’s most personal film. Essentially, it is an animated autobiography about the shy, sexually frustrated, pinball-playing aspiring underground cartoonist Michael Corelone (yes, it’s one of many references to Francis Ford Coppola‘s The Godfather). Michael attempts to make his way out of his warring parents’ Bronx home. As his much put upon Jewish mother and philandering Italian Mafioso father play out an urban “Taming of the Shrew,” Michael ambitiously sticks to plying his trade. Heavy Traffic is a paradoxical, heartbreaking, harrowing love letter to counter-culture urban freaks; replete with transvestites, amputees, interracial relationships, construction worker thugs, and God as a rapist. Bakshi is deep into Herbert Selby, Jr. territory here,leaving no demographic unoffended. Within this literal black comedy, the city streets are squalid and awash in Edward Hopper despair.

A beautiful scene depicts Michael in a dilapidated theater watching 1932’s Red Dust (probably the best film of both Clark Gable and Jean Harlow). Bakshi elevates stereotypes to sublime tragedy, reminding us that often, we choose to live up to those stereotypes. Artistically and emotionally, Heavy Traffic is arguably Bakshi’s greatest, most surreal accomplishment, which validates the argument that art is at its most significant, potent, and powerful when the artist depicts what he (or she) knows.

Like its predecessor, Heavy Traffic was an immediate hit, which led to the film with Bakshi’s biggest cult following and biggest controversy: Coonskin(1974). From its title alone, one can easily surmise intentional provocation. Premiering at the Museum of Modern Art, Coonskin did exactly what its producers probably hoped it would do: create an uproar. Theaters were picketed (mostly by people who had not seen the film), bourgeois audience members walked out of numerous showings, and there were even bomb threats. In a panic, Coonskin was shuffled from one distributor to another.

It is unfortunate that protestors failed to look beyond the vaudevillian, grotesque ethnic caricatures (of Jews, African-Americans, Italians, and women, who all still come off better than male WASPS). With a bit more intellectual investment, the offended may have recognized Coonskin as a brutal satire of blaxploitation films and Song of the South (Disney’s 1947 embarrassingly dated portrayal of an Uncle Tom named Remus, which is largely unavailable, except in the Deep South, of course). As in Heavy Traffic, Bakshi innovatively combines live action with animation[1] to create a stylishly artistic, gritty, urban surrealism. Visceral violence, bordellos, drug rings, and mafia exploitation of Harlem craft a narrative more haphazard than Heavy Traffic. Still, Coonskin satisfies as a highly original work, in spite of being (sloppily) promoted as something akin to a fireworks display. Scatman Crothers (who also voices in the film) sings the title song “Ah’m a N_ _ _ ger man, ” followed by the first line of dialogue: “F_ _ k you,” which sets the tone. Some consider Coonskin to be Bakshi’s masterpiece, and they may have a point, although the actual film is probably not as shocking as its reputation.

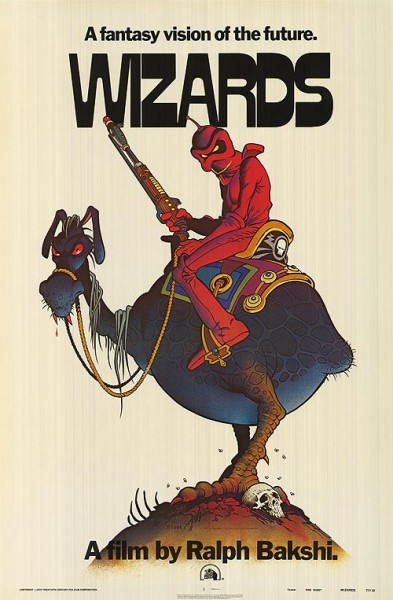

Wizards (1977) finds Bakshi in sword and sorcery fantasy terrain. As with most films of this type, the plot involves a conflict between good and evil, replete with fairies, elves, and warriors. Clearly inspired by the legendary fantasy artist Frank Frazetta, and worked on by, among others, Marvel comic artist Mike Ploog, Wizards will not be mistaken for Disney or George Lucas.

Third Reich allegories abound in this post-Holocaust fable, which brilliantly includes actual propaganda footage from Nazi rallies, along with Sergei Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky (1938). With this, and the high quota of violence and eroticism, Wizards is about as subtle as a pair of brass knuckles. As visually striking as it is,Wizards concentrates so much on its look—which is occasionally too layered–that the narrative spirals out of control. It’s not helped by redundant narration. The result is an uneven, but admirably relentless, film, which once was a midnight cult favorite but now appears to be relatively forgotten. In its ballsy political commentary, it certainly has to be off-putting to the rather sizeable right-wing faction of the Dungeons and Dragons crowd. Like most of Baskhi’s work,Wizards is simultaneously dated and ground-breaking.

Bakshi followed Wizards (1977) with the grandfather of all fantasy narratives: The Lord Of The Rings (1978). With the success of his previous work, Bakshi was given an astronomical budget (in 1978) of four million dollars (the box office take exceeded 30 million). Predictably, J.R.R. Tolkien’s elf fan boys were mighty upset with the news that the man behind that obscene Fritz the Cat would be directing. Per the norm, the fans were wrong when they protested that Bakshi would make a travesty of Tolkien. Actually, Bakshi’s adaptation is largely faithful to the first two books. Tim Burton made his (uncredited) Hollywood debut here as one of the animators. This was also the first animated film that was extensively rotoscoped. A few purists cried foul, but generally, critics and audiences disagreed. Bakshi originally conceived of using a Led Zepplin score for LotR, and one can only wonder how that might have affected the final work. Unfortunately, he could not negotiate rights to the rock band’s music and used Leonard Rosenman instead (a decidedly mediocre film composer).

At the time of its release, LotR was the longest feature-length animated film, with the exception of Fantasia (1940), which originally was a stateside flop. Bakshi and producer Saul Zaentz indeed took a considerable risk, which paid off, at least at the box office. The film was unfortunate to be made during a studio shakeup at United Artists, which resulted in a change of producers midstream and budget cuts, ultimately resulting in an unfinished work (originally, the plan was for a trilogy). The tension shows on screen, and too much is packed into the two-and-a-half hour running time. Minor flaws aside, it’s a beautifully mounted, innovative, ambitious production.

Like Wagner’s Ring Cycle, perhaps a perfect LotR only exists on the printed page. Peter Jackson’s admirable but too-zealous triptych is plagued with about thirty battle scenes too many and a lot of sickening doe-eyed close-ups of hobbits in the final entry (Jackson did pay homage to Bakshi in several admittedly “lifted” scenes).

Although a few Tolkien fans cried blasphemy because of cuts made in the narrative, Bakshi’s LotR established him as the most innovative big name in animation.

Surreal, psychedelic, and phantasmagorical, American Pop (1981) startles in its innovativeness. This well-written Western saga covers a family of musicians from the turn of the century until the 1980s. It is a collage of a cultural fantasia, mixing animation, footage from newsreels and documentary films, painting, and still photography. Bakshi’s legacy is in pushing the boundaries of what constitutes both animation and film. Bakshi is a juggernaut here, and American Pop is themost pronounced example of his art, standing as one of strongest examples of experimental American cinema (in either live action or animation). Unfortunately, animated films were in not in vogue during the 1980s, and such a force of innovation predictably confused several critics of the period. American Pop died at the box office, but has rightly become a cult classic.

Hey Good Lookin’ (1982), a coming-of-age tale set in the 1950s, was originally set to follow 1974’sCoonskin, having been started (and finished, at least as Bakshi was concerned) in 1975. In the original, only the main characters were animated, mixed with live action sets and actors. However, Warner Brothers, who were initially enthusiastic, changed their minds a week after the preview, convinced that American audiences would not accept a mix of live action and animation. (This was before 1988’s smash hit Who Framed Roger Rabbit?). After finishing LotR, Bakshi relented and resumed working on it as an entirely animated feature. Back in the familiar terrain of provocative social commentary, Hey Good Lookin’ is one of Bakshi’s least known ultimately underrated films, although it’s not perfect. Warners’ continued tampering with the film (replacing the original ’50s rock soundtrack with an ’80s retro-sounding score), harming it even further.

On the surface, Hey Good Lookin‘ seems to be a nostalgic trip, but as many artists have correctly surmised, nostalgia can often be a harmful crutch. Bakshi knows this, and calls out the inherent racism of a period that many feel would “Make America Great Again.” Naturally, in depicting racist stereotypes, Bakshi was accused of being racist and the film, which received mixed reviews, died quickly at the box office.

Co-produced by fantasy artist Frank Frazetta, Fire and Ice (1983) should have been a hit, which was of course what Bakshi was hoping for after two box office failures. It wasn’t, and proved to be another nail in the artist’s coffin.

Far simpler in plot than previous efforts, Fire and Ice was produced on a reduced budget of 1 million and took in less than half of that. It is entirely rotoscoped, and reviewers were beginning to sharply criticize the process. Despite a budget which compromised the production, pacing issues, and being aesthetically less ambitious in scale, Fire and Ice still has much to recommend it, including a innovative collaboration between Frazetta and Bakshi. The Limited Edition DVD includes a second disc with a documentary about the late Frazetta, whom Bakshi clearly had immense respect for.

After the failure of Fire and Ice, Bakshi disappeared from the scene until 1987, when he produced and directed many episodes of “Mighty mouse: The New Adventures.” Like Bakshi’s feature films, the series was highly innovative. Numerous critics noticed this time, and both Bakshi and his work rightly received accolades. Alas—only in America!—it all came toppling down thanks to a vile Methodist pastor and radical right-wing fundamentalist kook (is there any other kind of right-winger or fundie?) Bakshi’s ahead-of-his-time experiments flew right over the head of Puritan neanderthal Rev. Donald Wildmon, who saw only Satan hisself peering through Bakshi’s flowers, and a mouse wearing underwear.

Amazingly, Wildmon actually succeeded in his crusade, threatening sponsors of this “evil cartoon.” After one season, Mighty Mouse, despite having won numerous awards and a large viewer base, was yanked off the air.

Bakshi was well ahead of the game in crafting animation for adults. In 1992, he got his last stab with Cool World, the story of a cartoonist who enters an animated world with a curvy female toon who wants to become real. It was a disaster of the highest order. With the success of Roger Rabbit, Bakshi got the green light to finally direct a live action/animation feature. Unfortunately, and unwisely, Paramount did not follow the lead or model of Touchstone, who actually trusted Robert Zemeckis and left him alone. Paramount executives, under the lead of perennial hack producer Frank Mancusco, Jr. (who gave the world the Friday The 13th series, whether we asked for it or not), were determined to keep the film within a PG rating. Without Bakshi’s knowledge, Mancusco and Paramount commissioned numerous rewrites, cast Gabriel Byrne in the lead (Bakshi wanted Bradd Pitt, but Mancusco argued that Pitt lacked star potential), sabotaged the editing, and slashed the film’s budget.

Disgusted with Mancusco’s interferences, Bakshi actually punched his producer in the face. Unfortunately, Mancusco Sr. was the president of the studio. Bakshi was promptly blacklisted (and still is). Despite his attempts to disown the film, Bakshi was solely blamed for the critical panning and box office failure of Cool World. Bakshi has not made a feature film since.

Although the finished film is not quite as wretched as its reputation, it is easily Bakshi’s weakest effort. Tellingly, the film does not feel at all like a Bakshi. Even when Bakshi kept the narrative simple, as he did in Fire and Ice, his films were never as muddled or as crude as Cool World. It does have inspired moments of surrealism, a cool song from David Bowie and Kim Basinger, who, with Pitt, easily steals the show from Byrne (although some hated both her and her character).

Since 1992, Bakshi has produced a few animated shorts; but essentially, he was forced to retire. Still, he earned a place among the top tier of innovative American filmmakers.

These were good reviews! I’ve linked your work in our article about Wizards: https://alkony.enerla.net/english/the-nexus/sf-f-nexus/film-review/wizards-movie-1977-film-review-by-kadmon