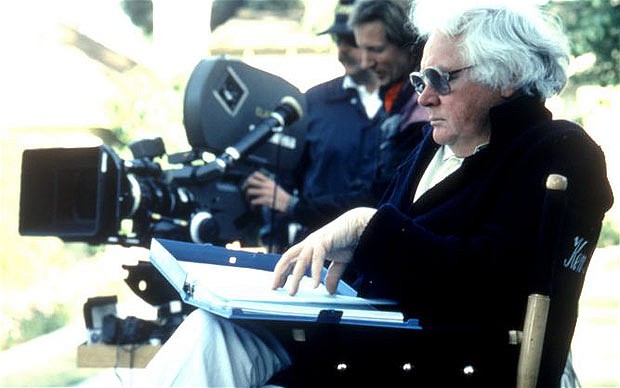

Parts I & 2 of a retrospective covering the theatrical feature films of Ken Russell (1927-2011) originally posted at 366 Weird Movies. Russell also produced an extensive number of documentaries, television films (many of which were composer biographies), and short films, which will not be covered here.

The late Ken Russell is undoubtedly one of the most ambitious and visionary filmmakers in the entirety of cinema. Excessive and flamboyant, he was often dismissed by mainstream critics. Russell was equally criticized in avant-garde circles for not having the courage of his convictions (meaning he wasn’t academically non-linear enough. There’s a reason Russell is often compared to the painter Francis Bacon, who continued painting surreal figurative works in the age of academic abstract expressionism). Admirably, Russell had no use for categorizations, but as idiosyncratic as he was, his execution did not always rise to the concepts in his work.

Russell’s strengths and weakness are evident in his first theatrical feature, French Dressing (1964). It’s a British caper comedy in the vein of Richaed Lester‘s Hard Day’s Night (1964). Initially it was a box office and critical failure. Russell’s penchant for surreal imagery and sharp edits is intact, although subtle by later standards. Even when subdued, Russell’s style doesn’t work for this kind of material, rendering the film heavy handed and narratively confused. However, it was original enough to develop a cult following, the first of many for Russell.

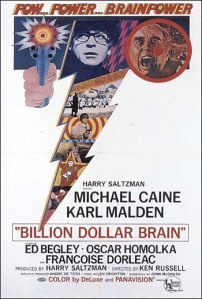

Believing French Dressing to be a misfire, Russell returned to the safety of television work for three years before reemerging with his next feature, Billion Dollar Brain (1967). It is the second sequel in the Harry Palmer series, with Michael Caine once again taking the title role. Russell proved just as ill-suited for this spy thriller trying to cash in on the James Bond fad, but Brain is also a standout in the franchise. Russell’s personal, icy stylization is in evidence throughout the film’s more fantastic sequences. Russell is most in his element with chaos, and most bogged down with restraints imposed by script and production. Despite its flaws, Billion Dollar Brain tries to play elastic with its genre, rendering it a fun mess.

Women In Love(1969) was the film that brought Ken Russell to worldwide attention (he was even nominated for Best Director). Many critics rank it as Russell’s most narratively satisfying film. Of course, Russell has D. H. Lawrence for a literary source and, despite its infamous nude wrestling scene between Oliver Reed and Alan Bates, the film is almost shockingly restrained and faithful to the spirit of Lawrence (out of necessity, Larry Kramer’s script, also nominated for an Academy Award, simplifies its literary source). Russell’s body of work, especially in television, reveals a highly erudite filmmaker who consistently approached literary themes and subjects with contextual fidelity, as opposed to surface literalism, which eventually branded him an irreverent enfant terrible.

Russell had a superb cast in Bates, Reed, Glenda Jackson (who won an Academy Award for her performance), and Jenny Linden. Billy Williams’ camerawork (yet another Oscar nominee) is lyrical, stark, and very much indicative of Russell to come.

After the box office and critical success of Women in Love, Russell plunged quickly into his first theatrical film with a composer as its subject. The Music Lovers (1970) focuses on Peter Tchaikovsky (Richard Chamberlain). With expressionistic sets, psychedelic lensing, elongated fantasy sequences (clearly inspired by : Kenneth Anger and Fantasia), along with a spiritually irreverent, high-pitched tone, this is Russell as we came to know him. Forsaking the typical program bio of the Nutcracker composer, Russell is not at all interested in pedestrian ideas of a “biopic.” Frank about its subject’s banality (he ejaculates while imagining the cannons of his god awful “1812 Overture” aimed at his enemies) and homosexuality, many critics, Roger Ebert included, labeled the film libelous. Chamberlain, who years later came out of the closet, in a far more accepting period, expertly slips into the title role. As Nina, the composer’s sexually frustrated wife, Glenda Jackson again excels in her second collaboration with Russell (she also spends much of the film in full frontal nudity, which, of course, inspired a few exploding heads in the “classical music” scene).

In all fairness to Russell, Tchaikovsky was tormented by his sexuality (in a undoubtedly hostile era). His death, publicly attributed to cholera, was probably a suicide, and he admitted a self-loathing for producing such commissioned works as the “Nutcracker” and “1812.” Indeed, Tchaikovsky’s best work is his lesser-known, personal compositions. Andre Previn conducts the London Symphony Orchestra with his usual craftsmanship. The film, like its subject, is aptly heart-on-sleeve.

The Devils (1971) is considered by many cult film fans to be Russell’s masterpiece, and it is almost unfathomable that it would be denied a 366 List entry. Russell, a convert to Catholicism, was aware of that religion’s inherent surrealism. Attracted to the aesthetics of Catholicism, as opposed to its dogma (I can relate), Russell locates the pulse of European excesses. For the traditionalist minded, The Devils is unadulterated blasphemy.

Loosely based on Aldous Huxley’s “The Devils of Loudun,”The Devils is the quintessential example of Russell excess (don’t dare look for a discernible plot). With opulent set designs by Derek Jarman (a frequent Russell collaborator), masturbating nuns, sadomasochistic demonic possessions, tormented priests of the Inquisition, and X-rated sexual fantasies, Russell is intentionally provocative, sparing no demographic from potential offense (including Roger Ebert, an atheist and former Catholic). Oliver Reed gives the performance of his life as a sacred erection, in duet with a bewitching Vanessa Redgrave.

Chicago Reader critic David Kehr found humor in The Devils and amusingly described it as a “David Lean remake of Pink Flamingos.” That’s about apt a summary as one can manage. More than forty years after its release, The Devils is no less subversive today, and has had spotty distribution in home video.

Russell followed The Devils with his only movie to receive a “G” rating. Starring Twiggy and adorned in an MGM color palette, The Boy Friend (1971) is an oddity in the Russell cannon. Based on Sandy Wilson’s 1954 play, Russell, with his charismatic lead, transforms it into a musical with an almost Wagnerian undercurrent (as if Busby Berkeley, clearly channeled here, isn’t demented enough). Twiggy’s charm serves as a counterbalance to Russell’s wandering camera. Christopher Gable co-stars (and will work with Russell again in 1989’s The Rainbow). Unfortunately, The Boyfriend was a box office flop, which prompted MGM to refuse Russell financial backing for his next film.

Taking out a second mortgage on his home, Russell financed Savage Messiah (1972) himself, which again finds the director examining artistic genius, here in the persona of French sculptor Henri Gaudier (Scott Antony). With Russell’s lifelong, obsessive passion for his subject, Savage Messiah is an authentic labor of love. Derek Jarman again serves as Russell’s art director, endowing Savage Messiah with Russell’s over-the top-visual sensibility (including an amorous Helen Mirren in a pop-colored cabaret). It is also an emotionally rich film focusing on the romance between Gaudier and Sophie Brzeska (Dorothy Tutin), which makes it all the more disappointing that MGM failed to promote it in distribution. Savage Messiah is, paradoxically, one of Russell’s most accomplished and least known works.

Mahler (1974) is another highly personal film for Russell, which I previously wrote about here.

Starring The Who, Ann-Margaret, Oliver Reed, Elton John (as the Pinball Wizard), Eric Clapton, Jack Nicholson, Tina Turner (as the Acid Queen), and Robert Powell, Tommy (1975) is undoubtedly Russell’s most famous film. Based on the Who’s 1969 rock opera, many critics accused Russell of preferring spectacle to substance. Others felt Russell’s film was a too literal approach. Tommy divided both fans and critics alike, and still does. The flaws are more the Who’s than Russell’s. With his operatic tenets and sense to enough to know that good taste is often at enmity with good art, Russell makes Tommy a powerful, one-of-a-kind experience, with each act topping its predecessor, building to an aptly histrionic crescendo. Disorienting, sensual, and filled to the brim with salted pain, Tommy is that rarity of rarities: an artistically authentic opera and musical experience.

Reed, unleashed again, proves an ideal collaborator, and Ann-Margaret deservedly earned a Best Actress nomination for her performance as Tommy’s mother. Unfortunately, Roger Daltry is no actor, and his performance undeniably hinders the film.

Tommy is already a deserving List Candidate and hopefully will be canonized sometime in the future.

Lisztomania (1975) is Russell’s idiosyncratic take on composer Franz Liszt. It is also an official List entry, found here.

Under-directed by Russell and physically miscast, ballet star Rudolf Nureyev still convinces as the titular Valentino (1977). A mix of alarming self-control and unfettered hyperbole, this uneven film disappointed Russell fans who wanted something more experimental in the vein of Mahler and Lisztomania. It also disappointed cinema history buffs and Valentino fans who wanted (but should not have expected) something more orthodox.

Despite flaws, Valentino is a beautiful film and accessible, if not constrained by historicity. Russell treats this subject no differently than others, including religion, as a mix of fantasy, facts, legend, and folklore.

Valentino was Russell’s biggest budgeted film to date and was a resounding flop at the American box office (it did considerably better overseas). It has since developed a cult following and recently has been released on Blu-ray, although the transfer has received mixed reviews.

Altered States (1980) was such an extravagant affair that its script writer, Paddy Chayefsky, disowned the film after seeing Ken Russell’s finished cut. It is one of two films Russell made for American studios and his last film to (barely) make a profit statewide. It is a Certified 366 Weird entry.

Russell’s second U.S.-made film was 1984’s Crimes of Passion. Starring Kathleen Turner and Anthony Perkins, Crimes was as divisive as any of Russell’s other work. It was primarily panned by critics and died at the box office, but has garnered enough of a cult following to warrant Arrow’s upcoming deluxe Blu-ray release, which will include Russell’s unrated director’s cut (the theatrical version is “R” rated).

With a new level of serious sleaze, Russell’s Crimes is a “hallelujah” to bad taste. Turner, as China Blue, sears. Perkins is in full twitchy ham mode and is equally fun, consistently chewing the scenery. Maddening, and yet also showing restraint, Crimes feels sincere in its mockery of hypocritical sexual mores.

With a budget of 4.5 million, Gothic (1986) took in less than a million. It is also a 366 List entry.

Ken Russell’s contribution to Aria (1987) is undoubtedly a highlight in this Fantaisa for adults. Russell joins directors Robert Altman, Jean-Luc Godard, Derek Jarman, Nicolas Roeg, Julien Temple, Bruce Beresford, Frances Roddam, Charles Sturridge, and Bill Bryden for this unique anthology. Aria is the kind of film that inspires American classical musical fans ( seeking only traditional interpretations) to bring out the white crosses and matches, slinging charges of Euro trash and sputtering about Regietheater ( which actually does quite well in Europe, as opposed to statewide opera houses which are frequently in the red). The rest of us, less constipated, will find much to savor here.

Russell tackles Puccini’s “Turandot,” which admittedly is the first time I’ve been able to stomach that hopelessly conservative composer. It is easy to see why Russell chose to interpret one of the most familiar tenor arias in all of opera, Puccini’s “Nessun dorma.” Russell uses British pin-up model Linzi Drew for a wincing, bejeweled surgical operation. It’s transfixing Russell blasphemy, which is what we have come to expect and hope for with him.

It was inevitable that the King of cinematic excess would pay homage to that blaspheming saint of excess, Oscar Wilde. 1988’s Salome’s Last Dance is taken from the infamous Wilde play. With tongue firmly in cheek, Russell makes a cameo as a photographer doing a shoot of Wilde’s play. That “outrageous evening” sets the film’s tone.

Profane, passionate, tacky, bawdy, gaudy, naughty, and wearing its theatricality on sleeve, Salome is delicious Russell, ranking with his best work. After all, what could be more campy than the Bible? Russell is completely in his elementhere; even stirring.

Glenda Jackson again stars (as the iron-hearted Herodias) and gives her role a degree of elegance. However, Imogen Millais-Scott steals the film in the dual roles of Salome and Rose (oddly, this is her only screen performance). Statford Johns (an excellent Piso in “I, Claudius”) plays Herod so effectively that Russell used him again in The Lair Of The White Worm. Salome is primarily set-bound, but never feels like it. It proved too literary and heterodox for American audiences, who avoided Salome altogether.

Lair Of The White Worm (1988) was another box office flop for Russell, taking in less than half its budget. It is also Certified 366 Weird.

Both Russell and Glenda Jackson reunite with D.H. Lawrence for 1989’s The Rainbow, based on the prequel novel to “Women In Love.” Jackson plays the mother of her character in the earlier film and she again proves to be Russell’s ideal. With one exception, Russell has an excellent cast in David Hemmings, Christopher Gable, and Paul McGann. However, critics were divided over the central performance of Sammi Davis as Ursula Brangwen, with some believing she held her own and others labeling her acting as amateurish.

Regardless, The Rainbow is one of Russell’s best-reviewed films (he mostly keeps his flamboyance in check). As expected, he does not shirk from themes of bisexuality. It is emotionally rich and never feels like a costume drama. Being Russell, it is also visually stunning, but not the equal of Women In Love. Good reviews, however, did not lead to box office results. The Rainbow tanked stateside.

In 1990, Russell took a break from directing and acted in Fred Schepisi’s The Russia House. Russell was effective in his role of a gay intelligence officer.

Whore (1991) is the film which ended Russell’s financing possibilities. It was promoted as an alternative POV to the slick, sanitized display of prostitution in 1990’s Pretty Woman. Knowing the title alone would provoke, distributors came up with the tagline “if you can’t say the word, just see it.” It didn’t work. What distributors did not count on was the American preference for the slick and sanitized.

With a limited budget to begin with, Whore was released with an NC-17 rating. Russell protested loudly, knowing such a rating would doom it at the box office. Critics were divided over the film and the performance of Theresa Russell (no relation to the director). An adaptation of the play by David Hynes, Whore is actually a subtle entry in Russell’s oeuvre, which is part of its problem. It’s too subdued and visually orthodox. With a succession of box office failures and the highly publicized ratings battle over Whore, Russell was no longer considered bankable. He retreated to television, shorts, and documentaries.

After an 11-year absence, Russell directed his last feature in the home movie The Fall of the Louse of Usher (2002). Shot with a camcorder on his estate, using his own money, and utilizing friends for actors, this demented sequel to Poe’s “Fall of the House of Usher” went directly to home video and was primarily ignored by critics. To its credit, it’s almost indescribable, and shows what an imaginative director can do with almost no budget.

Trapped Ashes (2006) was Dennis Bartok’s anthology horror production, with each segment (all written by Bartok) being directed by different a cult filmmaker. Monte Hellman‘s entry is probably the best. Russell, as expected, delivers an over-the-top vignette about vampire udders. The problem with this anthology is not the directors, but the uninspiring writer. Russell camps it up and, despite a lackluster script, seems to be having fun one last time.

Ken Russell should have gone out in a blaze of glory. Instead, he lived long enough to see his brand of filmmaking as highly personal art become an obsolete whisper.

Thank you for the comments. I have an authentic passion for and identification with Russell’s work, which dates back thirty years. Admittedly, of the filmmakers I have absorbed, it is Russell who has had the most impactive influence on my own work in the medium of film. I frequently make pilgrimages to his altar.

Love this post. A friend of mine worked with Russell on several films (in costuming) and to this day remains a passionate advocate of Russell’s work. He really got me to delve deeper into Russell’s filmography.

Great post! I’m a huge fan of Russell — a very underrated filmmaker. Such a misunderstood artist. For example, “Whore” deserves some love — it’s little gem. I also thought “Crimes of Passion” was fantastic. Russell has this ‘touch of madness’ that appeals to my sensibilities.